Historical notes on the activities of anarchist partisans in the anti-fascist Resistance in Italy during World War II.

Italy formally surrendered to the Allies on 8 September 1943, though areas of central and northern Italy remained in the hands of the Germans and of the fascist Salo Republic. Anarchists immediately threw themselves into armed struggle, establishing where possible (Carrera, Pistoia, Genoa and Milan) autonomous formations, or, as was the case in most instances, joining other formations such as the socialist ‘Matteotti’ brigades, the Communist ‘Garibaldi’ brigades, the ‘Giustizia e Liberta’ units of the Action Party.

Twenty years of fascist dictatorship which, perhaps deliberately, labelled any sort of opposi- tion as ‘Communist’, exile, imprisonment and not least the quite special treatment that the post-fascist Badoglio government reserved for anarchists certainly helped make any immediate rebuilding of the organisational ranks of the libertarian movement all the more difficult. It was in this special context, marked by confusion and disorientation, that there took place a far from negligible haemorrhaging of some libertarians in the direction of the Action Party, the Socialist Party and sometimes the Communist Party. While anarchist participation in the partisan struggle was conspicuous, especially in terms of bloodshed, it also exercised little influence. This was due to the complete hegemony of social-democratic ideas across an arc of political groupings from liberals through to the Communists.

Here are details of anarchists in the anti-fascist partisan struggle in different areas across Italy from the time of the surrender:

Rome

In Rome, anarchists were to be found in several resistance formations, especially the one commanded by the republican Vincenzo Baldazzi who was well known to comrades as an old friend of famous Italian anarchist Errico Malatesta. In many cases they gave their lives in the Roman resistance. Among such were Aldo Eluisi, who perished in the Andentine Caves; Rizieri Fantini, shot in Fonte Bravetta; Alberto Di Giacomo alias ‘Moro,’ and Giovanni Callintella, both of whom were deported to Germany, never to return; Dore, a Sardinian by birth, perished in a mission behind the lines.

The Marche

In the Marche anarchists served in several partisan formations in Ancona, Fermo, Sassoferato and Macera (where Alfonso Pettinari, ex-internee and political commissar of a ‘Garibaldi’ brigade, met his death).

Piombino

Piombino, a steel town with a great libertarian tradition and a tradition above all of revolutionary syndicalism, was behind a popular uprising against the Nazis on 10 September 1943: among the anarchists who took part in the uprising, Adriano Vanni, who operated as a partisan in the Maremma and who was called upon to join the local CLN (National Liberation Committee, a body made up of a spectrum of anti-fascist parties) stands out.

Livorno

In Livorno, anarchists were among the first to seize the arms stored in the barracks and in the Antignano Naval Academy - arms used later against the Germans and the fascists. Organised inside the GAP (Patriotic Action Groups), they took part in guerrilla operations in the area surrounding Pisa and Livorno and were represented in the city’s CLN. Virgilio Antonelli distinguished himself in the task of liberating hostages and prisoners.

Apua

In Apua, the libertarian contribution to the resistance was consistent as well as crucial. The anarchist partisan formations active in the Carrara area went by the names ‘G. Lucetti’ (60-80 persons), ‘Lucetti bis’ (58 strong – these two groups named after the anarchist Gino Lucetti who was executed for attempting to assassinate Mussolini), ‘M. Schirru’ (454 strong – named after another anarchist and would-be assassin of 'Il Duce', Michael Schirru), ‘Garibaldi Lunense’ and ‘Elio’ (30 strong). After 8 September, anarchists (including Romualdo Del Papa, Galeotti and Pelliccia) led the attack on the Dogali barracks, seizing the weaponry and urging the Alpine troops to desert and join the partisan campaign.

In the nearby Lorano Caves, Ugo Mazzuchelli used these weapons to set up the ‘G. Lucetti’ formation of which he became commander: in the context of the Appian Brigade, its task was to see to its own funding and to help the populace in obtaining provisions by means of properly accounted for expropriations (robberies from capitalists). Having gone through the bitter experience of the Spanish Civil War and Revolution of 1936-9, in which the Communists turned against the anarchists and the workers to seize power, the most ‘experienced’ comrades were rightly mistrustful of them. Some Communist units in any event featured in episodes which bordered on impropriety. But it should be emphasised that the presence of libertarians and anarchists was discernible in virtually every formation, wherever they did not have a unit specifically their own, under one set of initials or another.

Among the incidents of ‘discourtesy’ we might mention the one that had Mazzuchelli and his men coming within an ace of death under machine-gun fire after they had been ready to lead the way across the Casette bridge, as the Communist partisans had been curiously insistent that they should.

In November 1944, following a sweep that cost it the lives of six men, the ‘G. Lucetti’ unit moved into the province of Lucca, which had by then been liberated. Mazzuchelli, along with his sons Carlo and Alvaro then crossed the front lines again to set up the ‘Michele Schirru’ unit which helped liberate Carrara before the Allies showed up. Among the many who distinguished themselves and whose names make up a list that we do not have the room here to catalogue were commandant Elio Wochiacevich, Venturini Perissino and Renato Machiarini. The blood-price paid by the people of Carrara was a high one: the anarchists managed to stamp the seal of social struggle upon the armed struggle for freedom and this endured for years after the liberation, with the co-operatives like the ‘Del Partigiano’ (consumer co-op), the Lucetti (rebuilding co-op) and several undertakings of a social nature (e.g. profit-sharing farming, teams of volunteers to work on the river channels, etc.)

Lucca and Garfagnano

In Lucca and in Garfagnano, in whose mountains anarchists from Pistoia and Livorno also operated (like Peruzzi, Paoleschi, etc.) the anarchists were to be found in the autonomous unit commanded by Pippo (Manrico Ducceschi). The province’s CLN had been founded by libertarian Federico Peccianti in whose home it held its meetings. Pippo’s unit captured a good 8,000 Nazi prisoners and sustained 300 losses. Libero Mariotti from Pietrasanta and Nello Malacarne from Livomo spent a long time behind bars in the San Giorgio prison in Lucca. Among the best known anarchists down there were Luigi Velani, adjutant-major of the Pippo formation, Ferrucio Arrighi and Vitorio Giovanetti, the last two in charge of overseeing contacts between the anti-fascist forces in the city.

Pistoia

Pistoia was the theatre of operations of the "Silvano Fedi"; anarchist unit, made up of 53 partisans who especially distinguished themselves in rendering assistance to displaced persons. An initial resistance group had been formed thanks to the work of Egisto and Minos Gori, Tito and Mario Eschini, Tiziano Palandri, Silvano Fedi and others; it performed a variety of missions which included procurement of weapons for other resistance units and the release of prisoners. The figure of its young commander, Silvano Fedi, was legendary: he perished in an ambush, (the circumstances are obscure) laid by Italians, as Enzo Capecchi who was there at the time has testified. (Capecchi was then commander before being wounded). The Fedi unit, under Artese Benesperi was the first one to enter Pistoia at the liberation.

|

| The last moments of some partisans, in front of a firing squad in Malga Zonta, 1944 |

In Florence, where Latini, Boccone and Puzzoli had earlier published a first, clandestine issue of ‘Umanita Nova’ the first armed band was formed on Monte Morello under the command of the anarchist Lanciotto Ballerini, who died in action. Official historians have rightly portrayed Lanciotto Ballerini as a hero but have ‘forgotten’ to mention he was an anarchist. Among others who perished in the fighting were, Gino Manetti and Oreste Ristori, both shot: Ristori, from Empoli, had earlier been active as an emigrant in Brazil and Argentina before fighting in Spain.

Arezzo

In the province of Arezzo the anarchists were especially active in the resistance in the Valdarno, in view of the rich anti-fascist tradition and tradition of social struggle in that area. The miner, Osvaldo Bianchi was part of the CLN in San Giovanni Valdarno, as a represen- tative of the anarchist groups: furthermore, Renato Sarri from Figline and Italo Grofoni, the latter in charge of explosive supply for the Tuscan CLN in Florence, distinguished themselves. Later a crucial contribution was made by Guiseppe Livi from Angliari who was active in the ‘Outlying Bands’ that operated in Vultiberina and who helped unmask a German spy who had infiltrated the partisans of Florence... and just in time.

Ravenna

In Ravenna, many anarchists fought in the 28th Garibaldi Brigade. Among the best known of them were Primo Bertolazi, (a member of the provincial CLN), Guglielmo Bartolini, Pasquale Orselli (who commanded the first partisan patrol to enter liberated Ravenna), Giovanni Melandri, (in charge of arms and food supply, and the victim, along with one of his daughters, of a German reprisal).

Bologna and Modena

In Bologna and Modena province the following were especially active... Primo Bassi from Imola, Vindice Rabitti, Ulisse Merli, Aladino Benetti and Atilio Diolaiti. Diolaiti, shot in 1944 in the Carthusian monastery in Bologna had had an active part in the foundation of the first partisan brigades in Imola, the ‘Bianconcini’ and in Bologna, the ‘Fratelli Bandiera’ and 7th GAP units. In liberated Modena, the very young Goliardo Fiaschi marched at the head of the 3rd ‘Costrignano’ Brigade of the ‘Modena’ Division, commanded by Araniano’ In Reggio Emilia, Enrico Zambonini, who had been active in the Appenines around Villa Minozzo, was shot after being captured along with the group of Don Paquino Borghi: he died shouting ‘Long live Anarchy!’ at the firing squad.

Piacenza

In Piacenza, prominent among others were the anarchists Savino Fornasari and Emilio Canzi who are linked, apart from anything else, by their all-too-curious deaths in road accidents. Emilio Canzi had earlier fought fascism back in 1920 in the ranks of the Arditi del Popolo and later in the Spanish Civil War: he had been captured by the Germans in France and then deported to Germany and then interned in Italy. After 8 September 1943, he organised the first partisan bands. Captured by the fascist Black Brigades, he was exchanged for other hostages. Resuming his post, he commanded 3 divisions and 22 brigades (a total of more than 10,000 men), with the rank of colonel and used the nom de guerre of Ezio Franchi. The La Spezia-Sarzana units operated in close conjunction with those of neighbouring Carrara. Two partisan groups were commanded by the libertarians Contri and Del Carpio. The La Spezia anarchists, Renato Olivieri (who had earlier been for 23 years a political prisoner), and Renato Perini died during gunfights with the Nazis while covering a withdrawal by their own comrades.

Genoa

In Genoa, anarchist combat groups operated under the names of the ‘Pisacane’ Brigade, the ‘Malatesta’ formation, the SAP-FCL, the Sestri Ponente SAP-FCL and the Arenzano Anarchist Action Squads. The attempt to set up a ‘United Front’ with all anti-fascist forces failed due to the Communists’ attempts to impose their own hegemony. Furthermore, anarchists had their own representation only in the outlying CLN ‘s and this obliged them to engage in the armed struggle while relying on their own devices. Activities were promoted by the Libertarian Communist Federation (FCL) and by the underground anarcho-syndicalist union the USI which had just resurfaced in the factories. The Genoese anarchists’ blood sacrifice in the resistance was really substantial with several dozens killed in gun battles, shot or perished in concentration camps. Omitting many others, we recall among the most active of them: Grassini, Adelmo Sardini Pasticio and Antonio Pittaluga. Pittaluga died on the eve of liberation: before surrendering and being killed, and finding himself alone, he threw a hand grenade at the German patrol that captured him. Also, the anarchist partisan Isidoro Parodi died in neighbouring Savona.

Turin

In industrial Turin, especially at the FIAT plants, the anarchist unit that went by the name of the 33rd ‘Pietro Ferrero’ SAP Battalion operated. Among our fallen comrades was Dario Cagno, who was sentenced to death by firing squad for his involvement in the killing of a fascist; there was also Ilio Baroni, originally from Piombino. Comrade Ruju, a partisan with the ‘De Vitis’ Division, turned down the military medal of valour which the State later offered him to mark his capture of no less than 500 German soldiers.

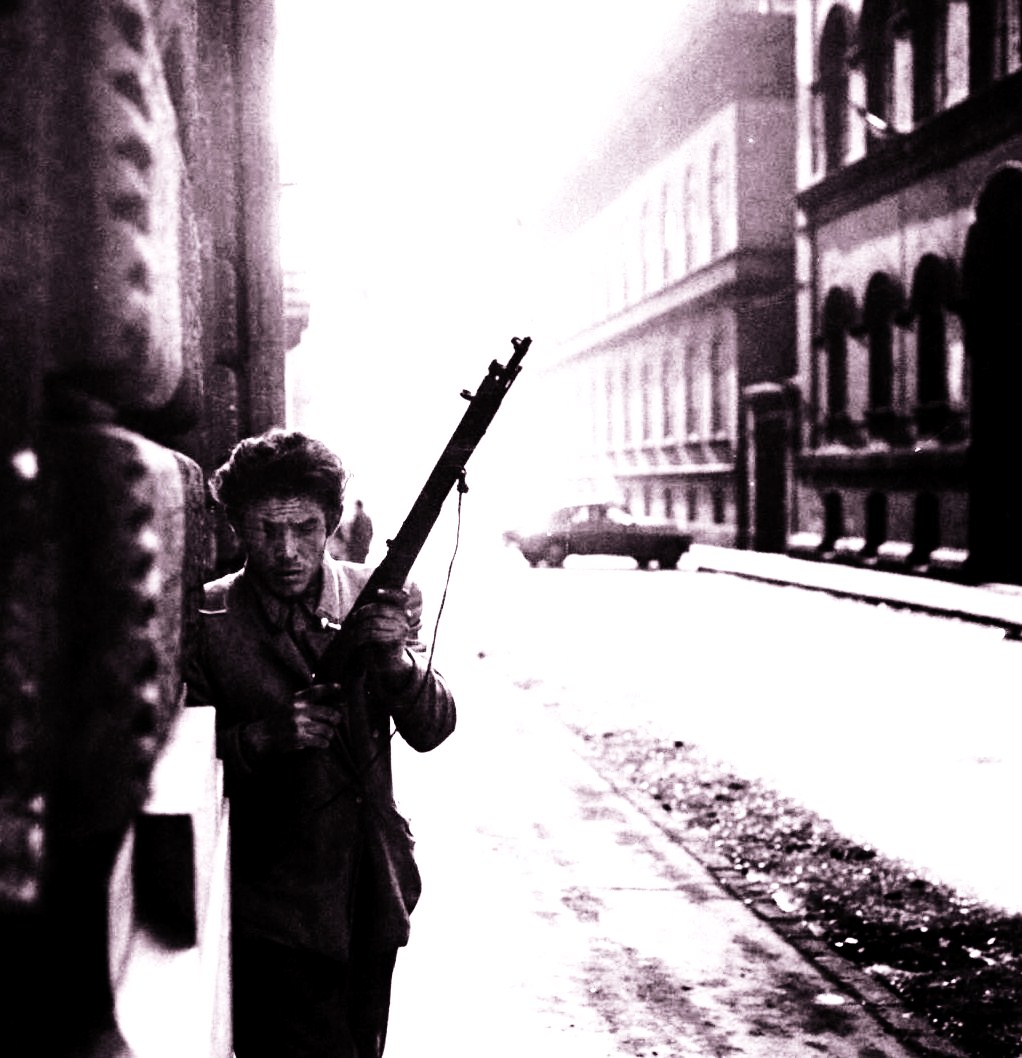

|

| Partisans parade in Milan following the Liberation, 1945 |

In the Asti area and in the Cuneo area, anarchists had a presence in the Garibaldi Brigades: the best known of them was Giacomo Tartaglino who had previously been involved in the Spartakist movement in Bavaria in 1919. In the Vencelli district, among several anarchists who distinguished themselves with their courage and daring was Guiseppe Ruzza who served with the ‘Valsesia’ unit commanded by Moscatelli. In Milan the threads of the clandestine struggle were taken up initially by Pietro Bruzzi who died after five days of torture, but without disclosing anything to the Nazis.

After his death, anarchists founded the ‘Malatesta’ and ‘Bruzzi’ brigades, amounting to 1300 partisans: these operated under the aegis of the ‘Matteotti’ formation and played a primary role in the liberation of Milan. Commanded by Mario Mantovani during the 1945 uprising, the two brigades distinguished themselves by their various raids on fascist barracks and also by their aid to the general population. Among the very youngest comrades was Guiseppe Pinelli who served with the GAP.

Pavia

In Pavia province operated the 2nd ‘Errico Malatesta’ Brigade led by Antonio Pietropaolo, who participated in the liberation of Milan. In Brescia, the anarchists were to be found in the mixed GL (Giustizia e Liberta') — Garibaldi formation: among the most active of them were Borolo Ballarini and Ettore Bonometti.

Verona

In Verona, the anarchist Giovanni Domaschi was founder of the National Liberation Committee (CLN). Arrested by the SS, he was tortured, had an ear cut off but refused to talk and so was deported to Germany where he disappeared in the concentration camps. Finally, in the Venezia Giulia-Friuli region many anarchists worked with the Communist formations like, say, the Garibaldi-Friuli Division. In Trieste, liaison was maintained by Giovanni Bidolo who later perished in the German camps along with another Trieste anarchist, Carlo Benussi. Also active was Turcinovich who, following a sweep, fled to Genoa where he fought with the local resistance. In Alta Carnia, where Petris and Aso (who perished in the attack on the German barracks in Sappada) had prominent positions, anarchists helped set up a self-governing Liberated Zone.

In all probability the number of anarchist fighting partisans who perished in the whole of central and northern Italy was in excess of a hundred.

The amnesty which was granted to fascists, and the social injustices of republican, democratic Italy later let anarchists (and not just anarchists) know that the spirit of the National Liberation Committee had been abandoned and the Resistance betrayed.

Taken and edited by libcom.org from an article by Giorgio Sacchetti for Umanita Nova, 7th April 1985. It was OCRed by Linda Towlson from the pamphlet Prisoners and Partisans: Italian Anarchists in the Struggle Against Fascism published by the Kate Sharpley Library, which contains loads more information about Italian partisans. And at £2 is highly recommended.

![Eurorepressione - Sulla conferenza a Den Haag sul tema "Anarchia" [corretto]](http://25.media.tumblr.com/tumblr_m0jvngOXtY1qa2163o1_1280.jpg)

![A tres años de la Partida de Mauricio Morales: De la Memoria a la Calle [Stgo.]](http://metiendoruido.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/mmacividad.jpg)

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento