The necessity for space is eminently political.

The places in which we live condition the

ways in which we live, and, inversely, our

relationships and activities modify the spaces

of our lives. It’s a question of daily

experience, and yet we seem incapable of

drawing the tiniest result from it. One only needs to take a walk through any city to

understand the nature of the poverty of our

way of life. Almost all urban space responds

to two needs: profit and social control. They

are places of consumption organized according

to the increasingly strict rules of a market

in continuous expansion: the security market.

The model is that of the commercial center, a

collective privatized space, watched by the

people and instruments provided by the

appropriate agencies. In the commercial

centers, an increasingly “personalized”

sociality is built around the consumer and his

family; now, one can eat, play with children,

read, etc. in these neon places. But if one

enters without any money, one discovers that

it is a terrifying illusion of life.

The same thing happens, more or less, in

the metropolises. Where can one meet for

discussion, where can one sit without the

obligation to consume, where can one drink,

where can one sleep, if one has no money?

For an immigrant, for a poor person, for a

woman, a night in the city can be long. The

moderates, comfortable in their houses, don’t

know the nocturnal world of the street, the

dark side of the neon, when the police wake

you up on the benches, when everything

seems foreign and hostile to you. When the

middle classes are enclosed in their bunkers,

cities reveal their true faces as inhuman

monsters.

Cities increasingly come to resemble

fortresses, and houses, security cells. Social

war, the war between the rich and the poor,

the governors and the governed is

institutionalized in urban space. The poor are

deported to the outskirts in order to leave the

centers to the offices and banks (or to the

tourists). The entrances of the cities and a

great many “sensitive” areas are watched by

apparatuses that get more sophisticated

every day. The lack of access to determined

levels of consumption – levels defined and

controlled by a fixed computer network in

which the data of banking, insurance,

medical scholastic and police systems are

woven together – determines, in the

negative, the new dangerous classes, who

are confined in very precise urban zones.

The characteristics of the new world order

are reflected in metropolitan control. The

borders between countries and continents

correspond to the boundaries between

neighborhoods or to the magnetic cards for

access to specific private buildings or, as in

the United States, to certain residential

areas. International police operations recall

the war against crime or, more recently, the

politics of “zero tolerance” through which all

forms of deviance are criminalized. While

throughout the world the poor are arrested by

the millions, the cities assume the form of

immense prisons. Don’t the yellow lines that

consumers have to follow in certain London

commercial centers remind you of those on

which some French prisoners have to walk?

Isn’t it possible to catch a glimpse of the

checkpoints in the Palestinian territories in

the militarization of Genoa during the G8

summit? Proposals for a nightly curfew for

adolescents have been approved in cities just

two steps away from ours (in France for

example). The houses of correction reopen, a

kind of penal colony for youth; assembling in

the inner courtyards of the popular

condominiums (the only space for collective

life in many sleeping quarters) is banned.

Already, in most European cities, the

homeless are forbidden access to the city

center, and beggars are fined, like in the

Middle Ages. One may propose (like the

Nazis of yesterday and the mayor of Milan

today) the creation of suitable centers for the

unemployed and their families, modeled after

the lagers for undocumented immigrants.

Metallic grids are built between rich (and

white) neighborhoods and poor (and… nonwhite)

neighborhoods. Social apartheid is

advancing, from the United States to Europe,

from the south to the north of the world.

When one in three blacks between the ages

of 20 and 35 get locked up in cells (as occurs

in the United States, where two million

people have been imprisoned in twenty

years), the proposal for closing the city

centers to immigrants here can pass almost

unobserved by us. And many may even

applaud the glorious marine military when it

sinks the boats of the undocumented

foreigners. In an interweaving of classist

exclusion and racial segregation, the society

in which we live increasingly looks like a

gigantic accumulation of ghettoes.

Once again the link between the forms of

life and the places of life is close. The

increasing precariousness of broad layers of

society proceeds at the same pace as the

isolation of individuals, with the

disappearance of meeting spaces (and

therefore of struggle) and, at the bottom, the

reserves in which most of the poor are left to

rot. From this social condition, two typically

totalitarian phenomena are born: the war

between the exploited, which reproduces

without filters the ruthless competition and

social climbing upon which capitalist

relationships are built, and the demand for

order and security, produced and sponsored

by a propaganda that is perpetually

hammered home. With the end of the “cold

war”, the Enemy has been moved, both

politically and through the media, into the

interior of the “free world” itself. The collapse

of the Berlin Wall corresponds to the

construction of the barriers between Mexico

and the United States or to the development

of electronic barriers for the protection of the

citadels inhabited by the ruling classes. The

criminalization of the poor is openly

described as a “war of low intensity”, where

the enemy, “the exotic terrorist”, here

becomes the illegal foreigner, the drug

addict, the prostitute. The isolated citizen,

tossed about between work and consumption

through those anonymous spaces that are

the ways and means of transport, swallows

terrifying images of treacherous young

people, slackers, cut-throats – and an

imprecise and unconscious feeling of fear

takes possession of individual and collective

life.

Our apparently peaceful cities increasingly

show us the marks of this planetary tendency

to government through fear, if we learn how

to look for them.

If politics is defined as the art of command,

as a specialized activity that is the monopoly

of bureaucrats and functionaries, then the

cities in which we live are the political

organization of space. If, on the other hand, it

is defined as a common sphere for

discussion and decisions regarding common

problems, then one could say that the urban

structure is projected intentionally toward

depoliticizing individuals in order to keep

them in isolation and lost in the mass at the

same time. In the second case, therefore, the

political activity par excellence is revolt

against urban planning as police science and

practice; it is the uprising that creates new

spaces for encounter and communication. In

either sense, the question of space is an

eminently political question.

A full life is a life that is able to skillfully mix

the pleasure of solitude and the pleasure of

encounter. A wise intermingling of villages

and countryside, of plazas and free expanses

could render the art of building and dwelling

magnificent. If, with a utopian leap, we

project ourselves outside of industrialism and

forced urbanization, in short outside of the

long history of removal on which the current

technological society is built, we can imagine

small communities based on face-to-face

relationships that are linked together, without

hierarchies between human beings or

domination over nature. The journey would

cease to be a standardized transport

between weariness and boredom and would

become an adventure free of clocks.

Fountains and sheltered places would

welcome passers-by. Wild nature could once

again become a place of discovery and

stillness, of tremors and escape from

humanity. Villages could be born from forests

without violence in order to then return to

being countryside and forest. We can’t even

imagine how animals and plants would

change when they no longer feel threatened

by human beings. Only an alienated

humanity could conceive of accumulation,

profit and power as the basis for life on Earth.

While the world of commodities is in

liquidation, threatened by the implosion of all

human contact and by ecological

catastrophe, while young people slaughter

each other and adults muddle through on

psycho-pharmaceuticals, exactly what is at

stake becomes clearer: subverting social

relationships means creating new spaces for

life and vice versa. In this sense, a “vast

operation of urgent demolition” awaits us.

Mass industrial society destroys solitude

and the pleasure of meeting at the same

time. We are increasingly constrained to be

together, due to forced displacements,

standardized time, mass-produced desires.

And yet we are increasingly isolated, unable

to communicate, devoured by anxiety and

fear, unable, above all, to struggle together.

Any real communication, any truly egalitarian

dialogue can only take place through the

rupture of normality and habit, only in revolt.

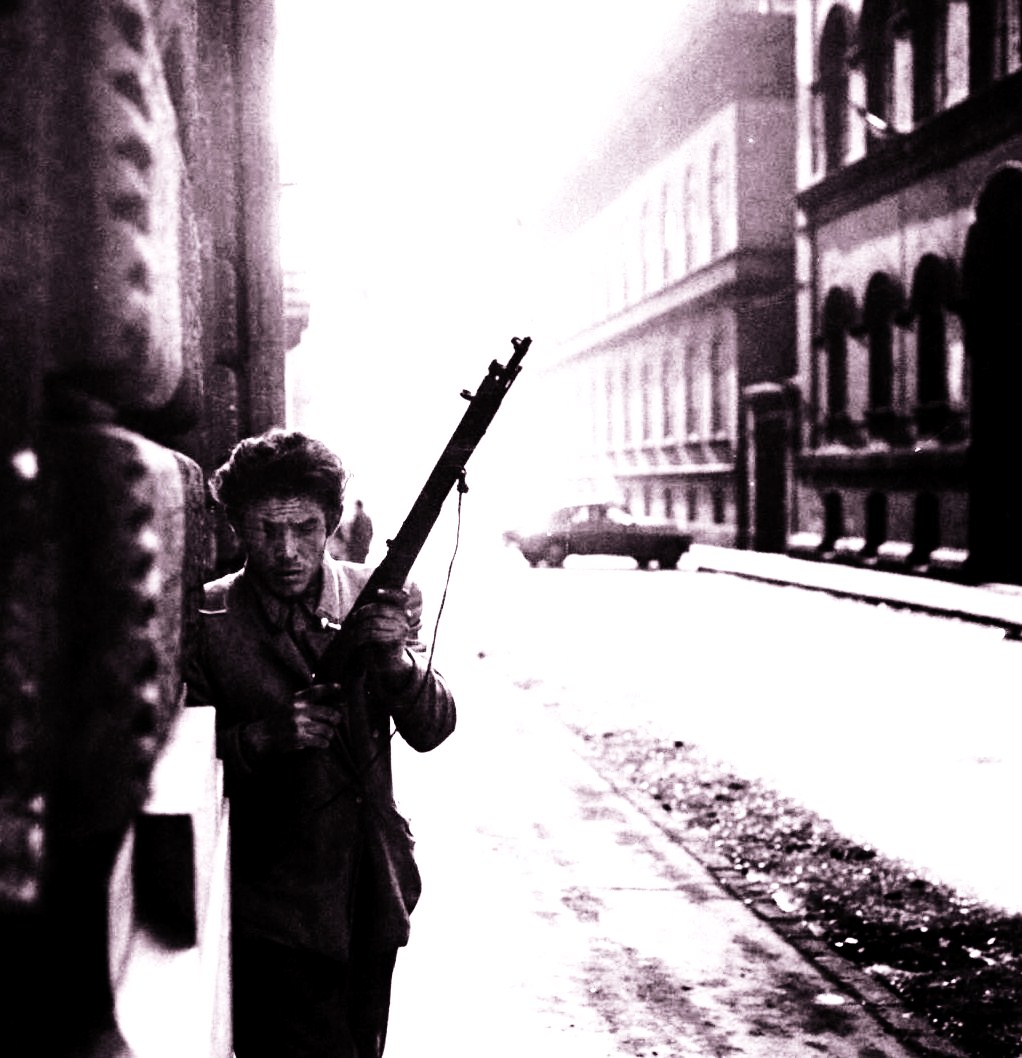

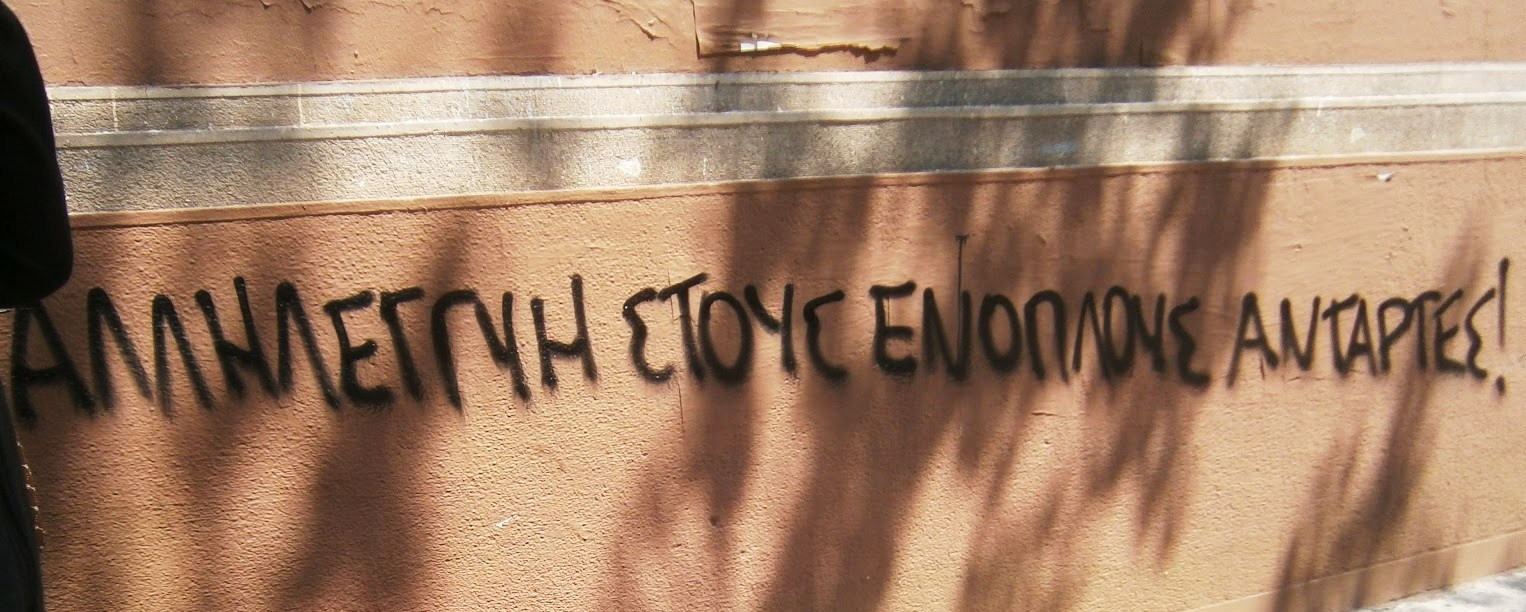

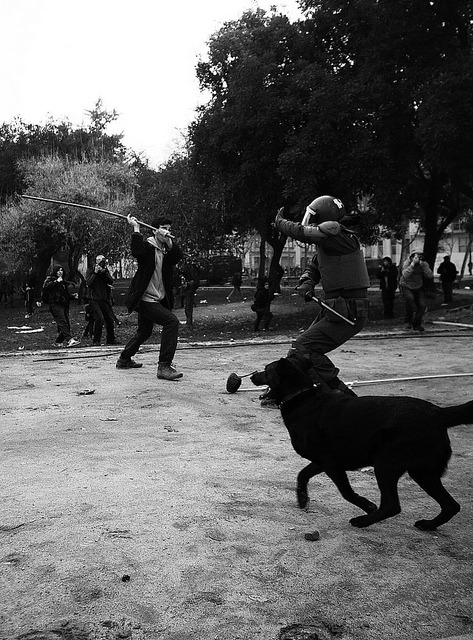

In various parts of the world, the exploited

refuse every illusion about the best possible

world, turning their feeling of total spoliation

against power. Rising up against the

exploiters and their guard dogs, against their

property and their values, the exploited

discover new and old ways of being together,

discussing, deciding and making merry.

From the Palestinian territories to the

aarch (village assemblies) of the Algerian

insurgents, uprisings free spaces for social

self-organization. Often the rediscovered

assembly forms are like applications of old

traditions of face-to-face relationships hostile

to all representation, forged in the pride of

other struggles, to the current agenda. If

violent rupture is the basis of uprisings, their

capacity to experiment with other ways of

living, in hope that the exploited elsewhere

will stoke their flames, is what renders them

lasting, since even the most beautiful utopian

practices die in isolation.

The places of power, even those that are

not directly repressive, are destroyed in the

course of riots not only because of their

symbolic weight, but also because in power’s

realms, there is no life.

Behind the problem of homes and

collective spaces, there stand an entire

society. It is because so many work year

after year to pay off a loan simply in order to

keep a roof over their head that they aren’t

able to find either the will or the space to talk

with each other about the absurdity of such a

life. On the other hand, the more that

collective spaces are enclosed, privatized or

brought under state control, the more houses

themselves become small, grey, uniform and

unhealthy fortresses. Without resistance,

everything is degraded at a startling speed.

Where peasants lived and cultivated the land

for the rich as recently as fifty years ago, now

the people of rank live. The current

residential neighborhoods are the most

unlivable of the common houses of thirty

years ago. Luxury hotels seem like barracks.

The logical consequences of this

totalitarianism in urban planning are those

sorts of tombs in which Japanese employees

reload their batteries. The classes that exploit

the poor are, in their turn, mistreated by the

system that they have always zealously

defended.

Practicing direct action in order to snatch

the spaces for life from power and profit,

occupying houses and experimenting with

subversive relationships is a very different

thing from any sort of more or less

fashionable alternative juvenilism. It is a

matter that concerns all the exploited, the

leftout, the voiceless. It’s a question of

discussing and organizing without mediators,

of placing the self-determination of our

relationships and spaces against the

constituted order, of attacking the urban

cages. In fact, we do not think that it is

possible to cut ourselves out any space

within this society that is truly self-organized

where we can live our own way, like Indians

on reservations. Our desires are far too

excessive. We want to create breaches, go

out into the streets, speak in the plazas, in

search of accomplice for making the assault

on the old world. Life in society is to be

reinvented. This is everything

. .

----EEtaken from “Saltar para o Desconhecido, #2”

Projectuality:

starting position that tries to have, from the beginning till the

end of the struggle, a global vision - but continuously looking at

the changing of necessities – of the elements that compose and

characterize it

Su gazetinu de sa luta kontras a sas presones #0

![Eurorepressione - Sulla conferenza a Den Haag sul tema "Anarchia" [corretto]](http://25.media.tumblr.com/tumblr_m0jvngOXtY1qa2163o1_1280.jpg)

![A tres años de la Partida de Mauricio Morales: De la Memoria a la Calle [Stgo.]](http://metiendoruido.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/mmacividad.jpg)

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento