from mainstream media

http://www.theolympian.com/2011/07/10/1719188/the-elusive-face-of-anarchism.html

DEFYING LABELS: Some local anarchists cheer violence against police and a news photographer; others deplore it.

Portrait of an anarchist: Daniel Kyle Wilson, age 20.

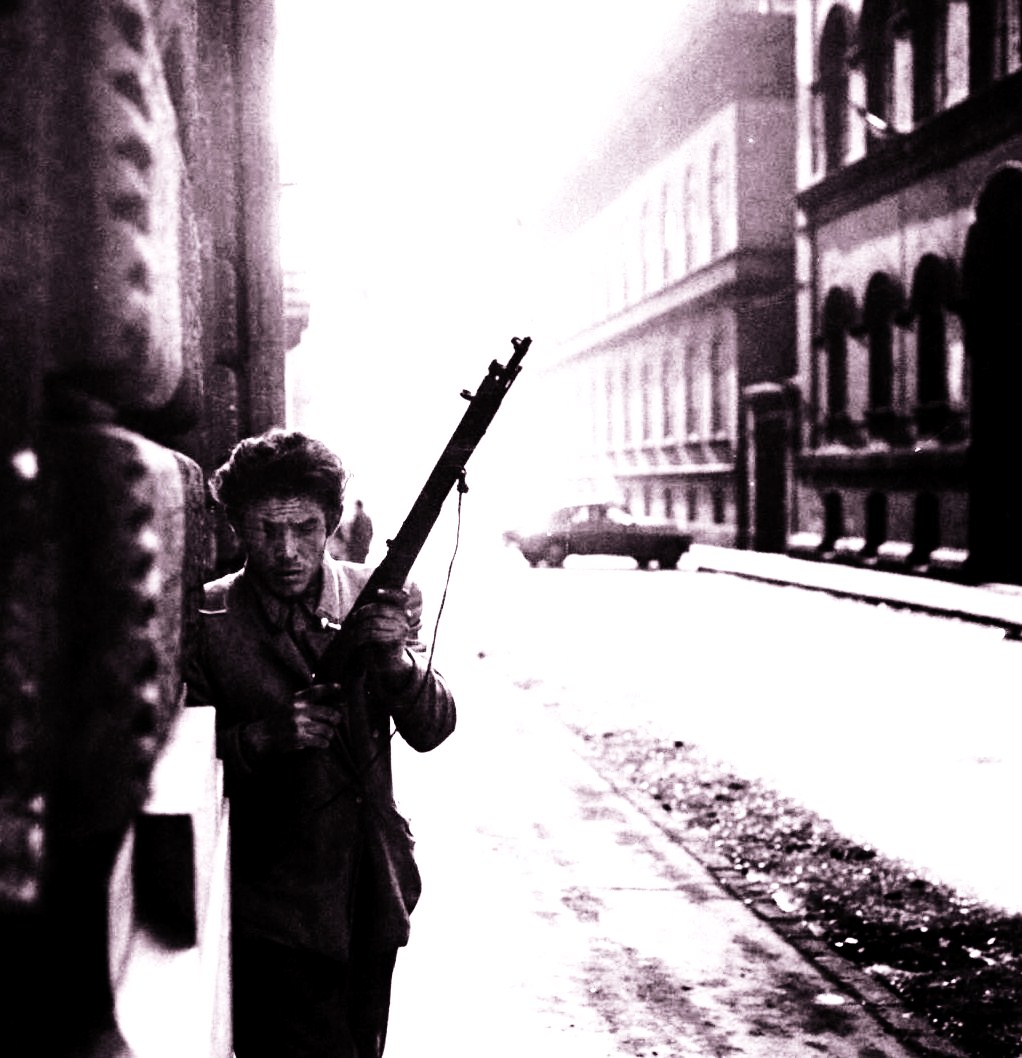

In a news photo taken May 1, 2008, he looks like a thrift-store ninja, ski-masked, wrapped in black from head to foot. His shoes are black, with three gray stripes.

He stands midstreet in downtown Olympia, flanked and followed by a parade of protesters, their faces turning toward him. At the edge of the image, a burly, uniformed man hurries up the sidewalk.

Wilson stands in profile. His arm is cocked. His fist clutches a rock. He aims it at the window of the U.S. Bank on Fourth Avenue and Capitol Way.

The bank represents everything he opposes: corporate power, hierarchy, an unjust pecking order, financial backing of “ecocide.”

A crime is coming. Tony Overman, veteran photographer for The Olympian, senses the moment and squeezes off a frame. The image will be published the following day.

A split second later, Wilson hurls his rock. Two other anarchists follow suit. The rocks shatter glass and land in the lobby.

Alarms. Adrenaline. The street goes crazy.

The burly man in uniform, a security guard for the bank, rushes to Overman.

“Did you see who did this?” the guard asks.

“Yeah,” Overman says.

His camera holds the frozen image of Wilson. Overman, caught up in the chaos, does something he’s never done before.

He shows the frame, not yet published, to the security guard. A police officer hustles up. Overman shows the photo again: Daniel Wilson and his striped shoes.

“The problem that I’m wrestling with is that I did the right thing as a citizen and I did the wrong thing as a journalist,” Overman recently reflected.

Officers chase the suspects. Wilson runs. Relying on the photo, police identify and arrest him, along with five others.

Protesters hinder the arrests, shouting and spitting at the cops.

“Go home and kill yourself and your family,” someone screams at officer Don Heinze.

A POTENT MIX

The May Day incident and its aftermath rippled through Olympia, starting a chain reaction and raising local tension in a community generally accustomed to political activism. Olympia houses the stew of state politics, three nearby colleges, energized students and a newspaper committed to local coverage.

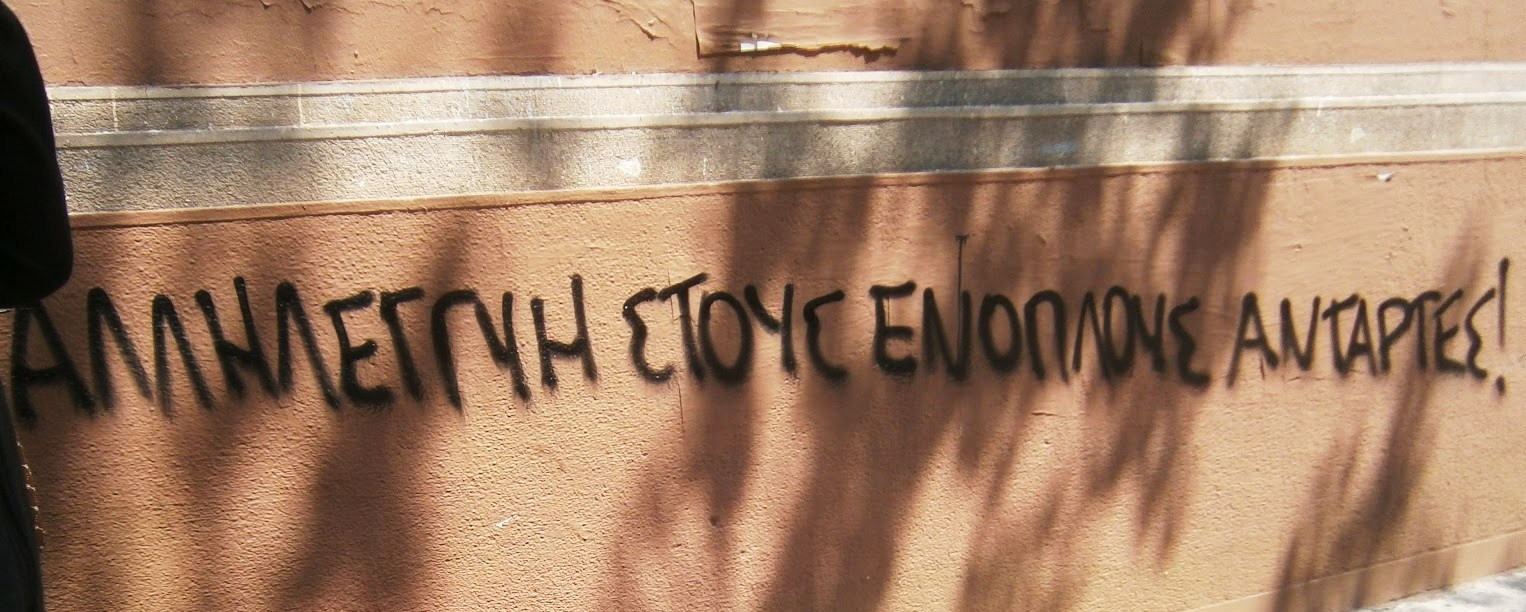

Protests and vandalism tied to anarchists have risen. On the website pugetsoundanarchists.org, anonymous writers have claimed credit for 18 incidents of vandalism in Tacoma and Olympia since December, along with similar acts in Seattle, Portland and Vancouver, B.C.

Banks and police facilities are the most common targets. Broken windows, banged-up cars, spray paint and ATM machines clotted with super glue are typical features.

In Olympia, an attack in March defaced a police substation.

“Two police vehicles were smashed up and the station itself received a few love taps that they won’t be forgetting anytime soon,” the website boasted.

Vandalism at several local banks followed in late March and April.

In June, the backlash from several incidents dating to the 2008 May Day protest boomeranged on Overman. Vandals targeted his home and the offices of The Olympian, spraying graffiti that labeled the photographer a “snitch.”

The newspaper and Overman responded with heat, noting their right and responsibility to cover public events. Overman said the attack on his home was more traumatizing than his stint covering the war in Iraq.

The recent incidents have angered the community, splintered activists into a roiling debate about the right and wrong kinds of protest, and drawn keen attention from city police.

“The line that has been crossed here in Olympia is that at times there is intentional crime being committed,” said Police Chief Ronnie Roberts. “To me it’s gang activity. That’s the way I look at it.

“We want to help be part of a community that allows for people to protest and to voice their concerns about issues that are important to them – but we don’t accept criminal behavior.”

SOURCES OF HATE

July 6, 2011: Daniel Wilson, now 23, sits outside an Olympia cafe, talking in long sentences and reeling off strings of injustice and inequity – the sorry state of the world.

“There are more sweatshops now than there were last year. More oil’s being taken out of the ground than last year,” he says. “There are mountains that are literally being cut down by Massey Energy, which is funded by Bank of America, which is why I (expletive) broke their (expletive) windows out, because I hate them. I hate them for their overdraft fees, I hate them for giving money to capitalists. I hate them for being a bank, for the bailouts.

“There’s numerous reasons for this class hatred. I can distinguish that from – I have loving relationships. And I’m really a nice person if you get to know me. Not a dangerous anarchist who’s going to screw you up.”

“I am a dangerous anarchist, I guess,” he says finally. “If ideas are dangerous.”

He wasn’t looking to get arrested in 2008. Maybe some protesters view arrest as a badge of honor or a means to draw publicity. Wilson doesn’t. These days, his chief concerns are his young son and his causes.

By circumstance, his recent history is intertwined with Overman’s. He understands the photographer’s anger.

“His house was just attacked,” Wilson said. “Right on. I’d probably be mad if my house was attacked.”

Wilson has lived in New Zealand, Canada and Mexico. He says he’s a 10th-grade dropout, but he reads voraciously, devouring academic and cultural histories. He says he works as a freelance graphic designer.

He readily calls himself an anarchist.

What does that mean? Who are the anarchists and what do they want? It’s a touchy question, muddied by words and multiple meanings. Wilson estimates that between 1,000 and 2,000 anarchists live in Olympia – but they’re not a matched set.

“Anarchy” implies disorder. “Anarchism” is a bit different. It’s an ideology driven by the notion that government and its formal systems are unnecessary, that individual choice should trump coercion.

Early anarchists include Emma Goldman and a pair of Russian writers, Mikhail Bakunin and Peter Kropotkin. The writer Noam Chomsky is another icon of the movement.

An anarchist might cleave to any of those figures, or none of them. Even those who accept the label argue over its meaning when they’re not blaming the media for stereotyping them. Looking for a way to blow an hour? Ask an anarchist what the word means.

“It’s almost as descriptive as using the term Christian,” said Drew Hendricks, 42, an anti-war activist based in Olympia. “There’s no central committee that’s gonna decide whether or not you’re an anarchist.”

Hendricks is a leader of OlyPMR (port militarization resistance). The group has held multiple demonstrations at the ports of Olympia and Tacoma, opposing the transport of military vehicles and hardware.

Participants include activists of every stripe, many of them peaceful protesters who do not advocate violence. Hendricks is one of them – he also watches police officers, making a point of taking their pictures during demonstrations.

Violence and anarchism are linked by history, but not synonymous. Some anarchists are pacifists. Some aren’t.

There are nonviolent “green” anarchists who plant “guerrilla gardens” by night on private property. Daniel Wilson counts himself in that group. Animal rights issues find their way into the anarchist mix, along with locally grown food, resistance to authority and fierce anti-corporatism.

Anarchists are paranoid, with some justification. They’re being watched.

A recent New York Times story recounted the FBI’s lengthy surveillance of a native Texan and self-described anarchist involved in local anticorporate protests. Rifling through the man’s recycling bin, federal agents found catalogs from Neiman Marcus and Pottery Barn.

Hendricks points to the recent revelation that a Fort Lewis employee, John J. Towery, infiltrated OlyPMR while acting as an informant for Tacoma police and the Pierce County Sheriff’s Department. A federal lawsuit filed against Towery and other agencies, citing civil rights violations, is mired in court.

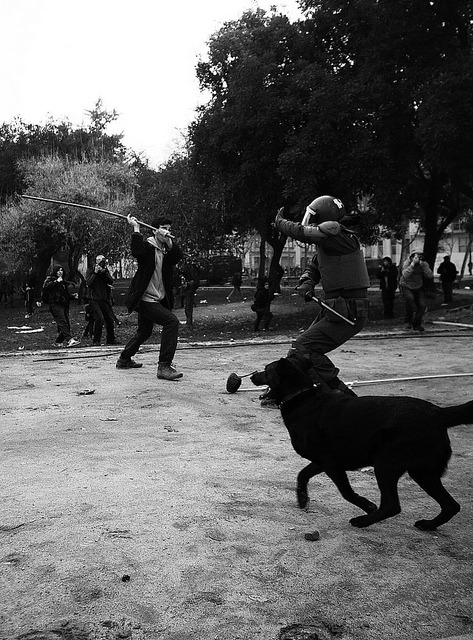

On the darker side, many anarchists have no problem with violence and vandalism. If police can do it, they argue, why can’t they?

“There are anarchists who will use threats and direct violence against the military and the police,” Hendricks said. “Generally speaking we call those people children. I’ve noticed a very strong correlation between the willingness to excuse the violence and the age of the person doing the excusing.”

Do anarchists act collectively? Roberts, the Olympia police chief, draws a distinction between organization and shared beliefs.

“Is there a big gigantic worldwide conspiracy? I don’t think that’s the case,” he said. “But I think there’s an ideology and a belief out there and people with very radicalized views that act out. Does stuff in Seattle drive behavior here? Stuff in Portland? Yes it does.”

The arrival of Roberts, hired late last year, put local activists on alert. The new chief came from Eugene, Ore., another community known for activism and a strong anarchist presence.

“This guy just became the chief in December or January, and the temperature is heating up,” Hendricks said. “So what time is it?”

Roberts said his service in Eugene has no bearing on his duties in Olympia.

“My goal here as a police chief is not about breaking the backs of the anarchists,” he said. “It’s about providing a community that’s safe for all the people to live in. If you violate the law, it doesn’t matter who you are – that’s going to bring police attention.”

EVERGREEN CONNECTION

Another facet of debate revolves around The Evergreen State College, an institution with a long tradition of liberal activism.

Some community leaders wonder whether the school fosters a culture that winks too readily at violent protest. Past arrests of protesters in Olympia have included Evergreen students, as well as students from South Puget Sound Community College and Saint Martin’s University in Lacey.

Not all anarchists come from Evergreen. Some of those arrested in the 2008 May Day protests weren’t students at all. They came from California.

Stephen Buxbaum, an Olympia city councilman, candidate for mayor, longtime state employee and part-time instructor at Evergreen, says the alleged linkage is unfair.

“It’s way too easy to create a false tension between Evergreen and the community,” he said. “We’re very interconnected in many more positive ways than negative ways.

“Any time that there’s a radical or anti-authoritarian type protest, to use that as an excuse to criticize all protests and all Evergreen students is in some ways a long-standing distortion of the relationship between the community and Evergreen.

“I think people at Evergreen are just as outraged as anybody is in this community. I don’t believe that Evergreen fosters and enables violent activity or criminal activity.”

Buxbaum added one more thought.

“People that are truly interested in social justice don’t operate anonymously,” he said. “Any time somebody puts on a mask, they’re separating themselves from the community.”

Peter Bohmer, a longtime Evergreen faculty member who has participated in anti-military protests at the Port of Olympia, says the blame-Evergreen chorus is too simplistic.

“It’s wrong to say it’s just Evergreen, which the media often does,” Bohmer said. “Evergreen is a really diverse school, actually.”

Bohmer teaches political economics, among other subjects. He is a proud liberal, devoutly anti-war, with an activist pedigree dating to the 1960s. That’s him, he says – but not Evergreen as a whole.

“My views are really critical of how society’s working,” Bohmer said. “But my views are not in the majority either among the faculty or the students there. Because I’m a teacher, I try not to use that power to influence people in my classes. I bend over backwards to be super respectful.”

Bohmer crossed swords with Overman in 2007 during an anti-military protest at the Port of Olympia. The incident, remembered by both men, echoed in the aftermath of the recent attack on the photographer’s house.

Overman was taking pictures at the scene, assigned by editors. Protesters were blocking road access, trying to prevent the transport of military vehicles. As he squeezed off frames, Overman heard Bohmer speaking.

“The words out of his mouth were, ‘This guy is working for the police. He’s trying to get you arrested – stop him from taking photos,’” Overman recalled. “That’s when they came in and physically tried to stop me from taking photos. (Bohmer) was three feet away. He said, ‘There’s a good chance you’re gonna lose your camera tonight.’”

Bohmer recalls the moment differently.

“In no way did I ever threaten him,” he said. “I did say to him that if he was photographing people who were doing these acts that they could be arrested for, that maybe he shouldn’t photograph their faces. I did say something along those lines. It was one conversation, probably a 30-second conversation.”

THE LINK IS MADE

Whatever the specifics, the idea had been planted. News photographs and arrests were linked in the minds of activists. The notion gained credence in 2008, at the May Day protest, when Daniel Wilson and others went to jail, a case strengthened by Overman’s photograph.

In one sense, it was just another assignment handed off by an editor. Overman doesn’t specialize in protests. He shoots all over Olympia, wherever the day’s duties take him – one day, a youth soccer game; another day, a protest.

Looking back, Overman wishes he’d acted differently on May Day 2008. Traditionally, newspapers (including The Olympian and The News Tribune, both owned by the same company) don’t release unpublished photos to police or anyone else.

The photo of Wilson sits in a gray area. It was published the following day – but it hadn’t been when Overman showed it to police in the midst of the riot.

“I’ve been doing this 30 years,” he said recently. “I’d never faced a situation of that intensity before. Emotionally I reacted in what seemed to be the right way when you see somebody committing a violent crime and run off.

“In hindsight, certainly if I had the time to stop and think about it, I wouldn’t have done it. I shouldn’t have done it as a journalist. I can’t be seen as an arm of law enforcement. I don’t have the protection that a law enforcement officer has.”

SERVING TIME

After his arrest, Wilson faced charges of malicious mischief and reckless endangerment. He made bail, accepted a plea deal, and left the country in mid-2009, shortly before his scheduled trial. A personal decision, he calls it.

He lived in British Columbia. In fall 2009, his partner got pregnant.

Wilson didn’t want to be a fugitive father, he said. He called the court and turned himself in a few days before Thanksgiving, starting a sentence of 150 days.

His stint caused a minor stir on activist websites: Wilson is a vegan. The menu at the Thurston County Jail didn’t cater to his needs.

“Help an Olympia anarchist get vegan food in jail,” one web posting said, urging calls to the jail, encouraged by Wilson.

From his cell, he teased the guards, telling them they were keeping him from the mother of his child, all for breaking a few windows. He was out by March 2010, back in Olympia, where the forests and the people suited him. His son was born in July.

Just as Wilson finished his jail stint, anarchist protesters, police and Overman tangled again.

The April 8, 2010, protest decried police brutality, including the 2008 fatal shooting of Jose Ramirez-Jimenez by Olympia police officers (prosecutors had determined the shooting was justified).

Again, masked anarchists marched. Again, Overman picked up the assignment and took pictures. One shot of a young woman spray-painting a street sign touched off a confrontation.

The woman, Jami Williams, turned on Overman and sprayed his camera and his face just as he squeezed off a frame. Protesters surrounded Overman, knocking his cellphone out of his hand before he could dial 911, according to a police report of the incident.

Once more, he was caught between the professional and the personal. He managed to contact police and report the attack. Police asked if he had a photo of the protester who’d attacked him. Overman, remembering 2008, hesitated.

Officers said he was the victim of a violent crime. He had every right to report it. Overman showed them the picture. Williams was arrested and charged with misdemeanor assault. Police ultimately arrested 31 people in connection with the protest.

Williams was ordered to pay restitution for damaging a camera lens. Overman said he never bothered to collect the payment.

AFTERMATH

The June 9 vandalism at Overman’s home, coupled with the attack on The Olympian offices, continued the argument. Police haven’t identified the perpetrators. Daniel Wilson says he wasn’t one of them and doesn’t know who was.

The photographer and the anarchist met again June 15, at a rally in support of Overman at The Olympian office. Wilson rode in on a bicycle. A group of photographers – colleagues of Overman – snapped pictures and video. One piece of video caught the following exchange.

Wilson: When I asked the police, they told me they got the photos from a journalist from The Olympian. And it turned out that journalist was you.

Overman: Right, they were published in the newspaper and on the website.

Wilson: Yeah, yeah, but what they said is you went the extra mile and that you gave it to them.

Overman: I did not give – I did not give anyone anything.

Other activists condemned the attack on the paper and the photographer. Drew Hendricks was one of them. He spoke to Overman personally.

“I told Tony I was ashamed this was done in the name of Anarchy,” Hendricks wrote on Olyblog, an independent media site based in Olympia. “It isn’t anarchist to do this; it is terrorism, the very opposite of respect for autonomy and the very essence of coercion.

“Tony and I both use public photography of police, he for his employment and I for my activism.”

Another activist, Wally Cuddeford, voiced similar views in a long column for Works In Progress, another local publication.

“I don’t appreciate who Overman works for,” Cuddeford wrote, “but photography of public events in public places for the sake of reporting on these events publicly is a valid occupation and a good way to feed one’s family.

“Let’s not mince words – even setting aside moral arguments, from a purely tactical position, this action does not make any sense at all. Even if Overman had turned over his photos to the police, it’s unclear what these anarchists hoped to gain through all this. …

“The anarchists’ failure to analyze the situation critically is not Tony Overman’s fault, and there is no justification for terrorizing him.”

»

Log in or register to post comments

Comments

Sun, 07/10/2011 - 5:36pm — indrid #

garbage garbage garbage garbage

Log in or register to post comments

Sun, 07/10/2011 - 7:44pm — brer rabbit #

Photographer will face discipline for violating trust of readers

The most precious attribute of any news organization is its credibility. Readers and viewers must know that we report events accurately and honestly to the best of our ability.

Maintaining our credibility also requires that we tell you when we’ve failed to live up to those standards. This, unfortunately, is one of those occasions.

In the aftermath of violent acts by protest marchers in 2008 and 2010 in downtown Olympia, we stated repeatedly that neither The Olympian nor Tony Overman, our photographer who covered the protests, ever supplied unpublished photos of protesters to police.

That’s not true. We regret that we misled our readers.

As reporter Sean Robinson discovered in researching today’s Page One story about anarchists in the region, Overman allowed police officers to view photos of protesters committing acts of violence during both marches. In each case, police used the photos to identify and arrest protesters.

In sharing those photos, Tony violated our long-standing policy of refusing to release to law enforcement agencies photographs and other material that have not been published in print or online.

We have that policy to ensure that we can be independent, unbiased observers of what goes on in our community. We are not an arm of any law-enforcement agency.

But applying such a policy is fraught with complications, and reasonable people can disagree about the appropriateness of Tony’s decisions. In the heat of violent confrontations, Tony held evidence of people breaking the law in his own hands, on the memory card in his digital camera. In a split-second decision as he watched people committing violent acts and in one case was assaulted himself, he chose to let police officers look at the photos on his camera’s view screen. That violated our policy.

But what happened after the protests is more disturbing. For three years Tony did not tell his editors what he had done, insisting that police had access only to photos published online or in the newspaper. That’s true, as far as it goes. The photos he shared with police eventually were published. But at the time police viewed them, they existed only on Tony’s digital camera. By omitting those facts, he misled our readers, as well as his editors and colleagues.

Since that time, local activists have continued to complain that Tony gave police the photos. Tony continued to deny it.

Tony has struggled about the decisions he made.

“The problem that I’m wrestling with is that I did the right thing as a citizen and I did the wrong thing as a journalist,” Tony told Robinson in a recent interview.

Last month, someone painted an anarchy symbol on Tony’s home, painted “Overman snitch” on his truck and slashed its tires. The Olympian’s building was similarly defaced.

Many in the community, including photojournalists and co-workers, rallied around Tony. He repeatedly told questioners that The Olympian had not given unpublished photos to police. Even when confronted at a June support rally by one of the protesters his photos helped to convict, Tony insisted again: “I did not give – I did not give anyone anything.”

Still, nothing Tony has done justifies what has been done to him. He was assaulted with spray paint, and his home, truck and camera were damaged by vandals who hide behind dark masks and call themselves anarchists.

Over the years he has worked in Olympia, Tony has earned the respect of his colleagues and many people in the community for his excellent photography and his professionalism. I’m convinced that these incidents represent an aberration in an otherwise unblemished career. Tony will be the subject of a disciplinary action. Then we’ll move beyond this, and Tony will be back out again doing what he does best – reflecting our community through the lens of his camera.

Read more: http://www.theolympian.com/2011/07/10/1719209/photographer-will-face-dis...

![Eurorepressione - Sulla conferenza a Den Haag sul tema "Anarchia" [corretto]](http://25.media.tumblr.com/tumblr_m0jvngOXtY1qa2163o1_1280.jpg)

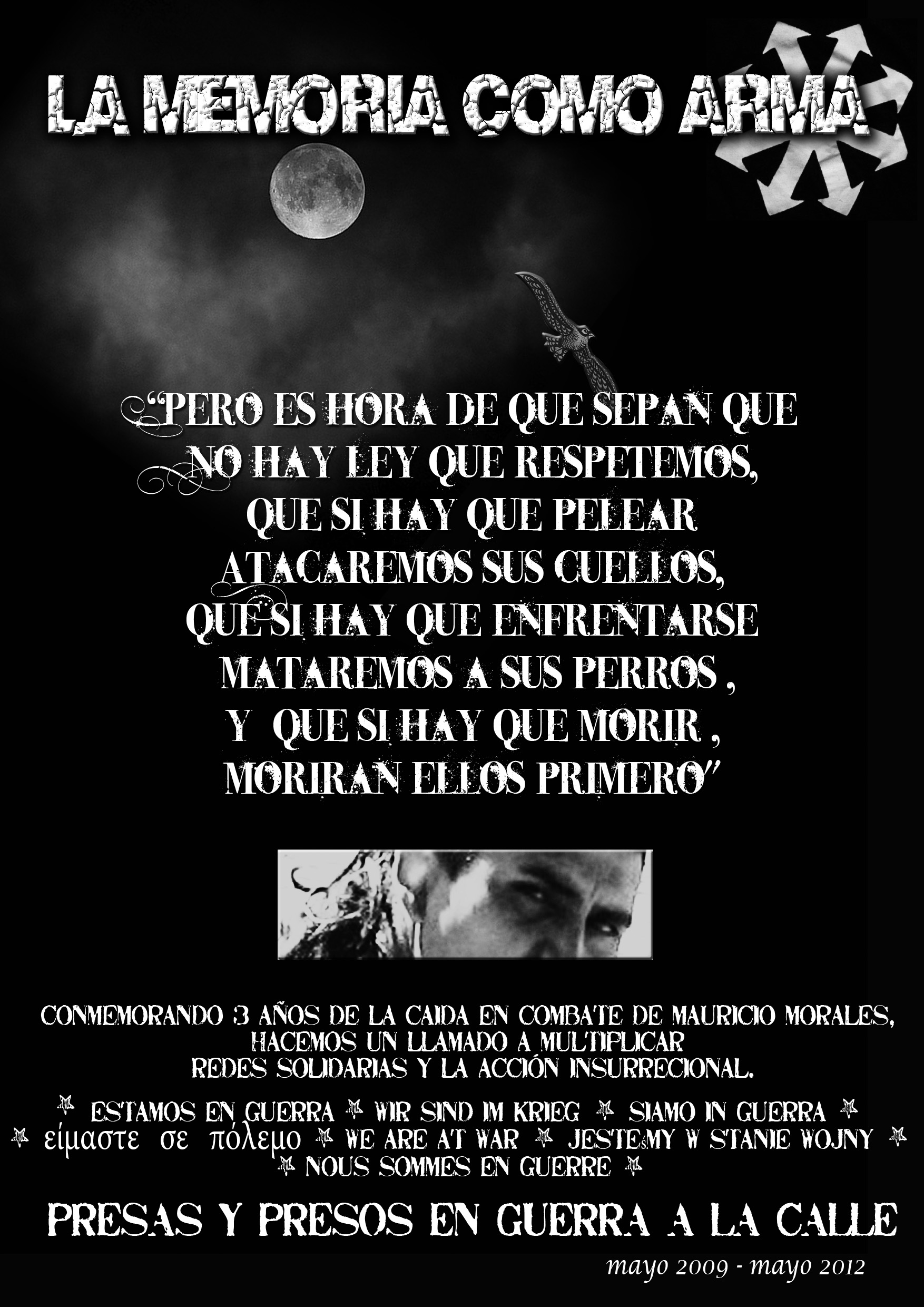

![A tres años de la Partida de Mauricio Morales: De la Memoria a la Calle [Stgo.]](http://metiendoruido.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/mmacividad.jpg)

Solidarity with comrades in Olympia!

RispondiEliminaTruly sickening how the police are repressing them. We think stories like Sacco and Vanzetti are things of the past but history repeats. Against-the-system activists will always find themselves watched/stalked by the pigs.