During the last 10 years, a lot of comrades in different countries have participated in the struggle around the question of migration, whether it be about the struggle of paperless people to get regularized, the struggle around housing in poor neighbourhoods, the struggle against raids on the street and on the public transport or the struggle against the detention centres. Often these have led to a repetition of certain impasses or to powerlessness regarding possible interventions.

A recipe does not exist, but we do consider it necessary to break with some militant mechanisms which have too often made us struggle on an activist base lacking perspectives or agitate under the directions of authoritarian groups, with or without papers. These thoughts simply want to draw up the balance of struggle experiences and to work out some possible tracks for the development of a subversive projectuality around migration and its management, a projectuality which we can call ours.

Beyond the illusion of the ‘immigrant’

Having a closer look on the protagonists of a social conflict and subordinate them to more or less militant sociological analyses is a classical approach towards an attempt to understand the context of a social conflict and to intervene in it. Not only does this approach focus upon finding the answer to the mysterious question “who are they?” instead of examining ourselves about what we want, it is as well based upon some doctrines which disturb our critical reflection. Next to the usual leftist racketeers who are desperately looking for no matter what political subject which can bring them to the head of a resistance, a lot of sincere others are to be found alongside the paperless people. But since they consider the specific situation of the paperless as something exterior, they are mostly rather driven by an outrage instead of by a desire to struggle together with those who share a common (although not exactly the same) condition: exploitation, police control on the streets or on the public transport, housing in the outskirts or in the neighbourhoods which are being upgraded, illegal activities which are part of the survival techniques. Both of them often reproduce all of the divisions which are useful to the domination. Creating a new general image of the immigrant-victim-in-struggle equals the introduction of a sociological mystification which does not only hinder every common struggle but as well strengthens the states grip on all of us.

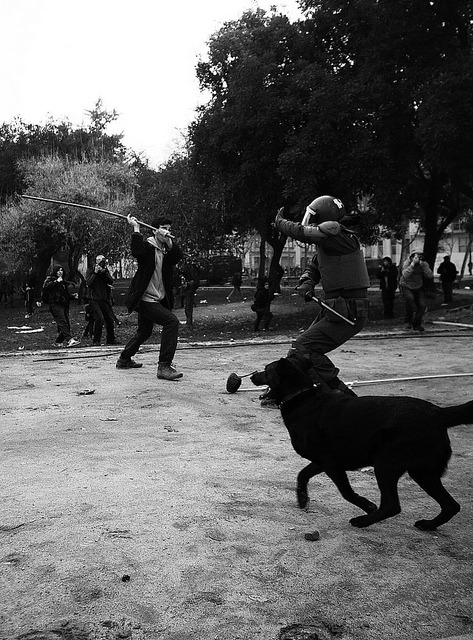

Libertarian or radical activists (who nonetheless have a certain intuition about what could be a possible common track) are fairly often not the last ones swallowing this pill in their need of collectivity or in the name of the autonomousness of the struggle, as if the struggle is put up by some sort of homogeneous block instead of by individuals, potential accomplices at least against a certain oppression. In relation to the paperless people all of the sudden the methods of struggle (self organisation, refusal of institutional mediation, direct action) became way more relative. The good Samaritan will always appear to explain, using some classical arguments out of the militant tirade, that breaking the windows of an air company which deports during a manifestation will bring the paperless ‘into danger’ (them who nonetheless face up to the police day by day); that the struggle against fascists (e.g. the members of the Turkish Grey Wolves), nationalists (e.g. certain refugees who came here after the disintegration of former Yugoslavia) or priests (e.g. the priest who ‘refuges’ the paperless in ‘his’ church to afterwards kick them out, the Christian associations which take up the vile task of the state like Cimade, Caritas International or the Red Cross) ends at the doorstep of the paperless collectives; that you can spit into the face of a French or Belgian ambassador but not into the face of a Malian one which comes mediating a struggle that threatens to radicalise (idem the leftist politicians who are generally considered unacceptable but being tolerated in the name of a false unity which is demanded by some chief of a paperless collective).

It is known to everybody that a struggle always departs from the existent and that the initial differences often differ a lot (e.g. the relation towards the trade unions in the major part of the struggles concerned with exploitation), but according to us it’s all about going beyond those in a subversive dynamic. We will certainly not succeed in this by accepting the variety of authoritarian straitjackets – the goal is already in the means you acquire. Moreover because this relativism doesn’t lead towards a confrontation in the struggle but to some sort of reverse colonialism which makes the immigrants once more into an object with a supposedly different-being (“they” would be like that). In that case the misery is not intended to scare off but to excuse all renouncement.

The “innocent immigrant”, the passive eternal victim which is being exploited, arrested, locked up and deported is one of the most prominent characters of this ideological narrowing down. As a reaction to the daily racist propaganda which aims at giving the immigrant the role of the social enemy who is the source of all evil (from unemployment to unsafety and terrorism), a lot of people de facto deny the immigrant all criminal capacity. They aim at presenting the immigrants as being servile, begging for their integration with hopes on a less detestable place in the society of the capital. In this way thousands of refugees are being transformed into sympathetic and therefore integratable victims: victims of war, of ‘natural’ catastrophes and misery, of human traffickers and rack-renters. But what is forgotten are the changes these tracks make to individuals: they create solidarity, resistance and struggle which allow some of them to break the passivity which was attributed to them.

Surprise and embarrassed silence rule the leftist camp and her democratic antiracism when these ‘innocents’ defend themselves by all means against the faith imposed on them (e.g. revolts in detention centres, confrontations during raids, wild strikes…). The revolts expressed in a collective way might still be understood by some as “those deeds of desperation”, but a prisoner putting his cell on fire all alone is called a “maniac” whose deed most certainly does not constitute as part of the “struggle”. Hunger strikers in a church are wanted, not the arsonists or escaped prisoners from the detention centres; the people who have been thrown out of the window of a police station or drowned are being understood, but not those who resist against the police during a raid; parents of children attending school get helped with pleasure, in contrast to the bachelor thieves. The revolt and the individuals who revolt do not fit into the sociological framework of the immigrant-victim that has been made up by the good conscience of the militant with the aid of the academic parasites of the state.

This mystification hinders a more precise understanding of migration and the migration streams. Clearly, migrations in the first place are a consequence of the daily economical terror of the capital and the political terror of local regimes and their bourgeoisie, all of which give profit to the rich countries. Nevertheless it would be incorrect to state that only the poor proletarians migrate to the rich countries as is sworn to by the thirdworldists in their construction of the immigrant-victim subject. The migrants who succeed in entering the gates of Europe clandestinely are not necessarily the poorest (since those are forced to internal migrations to the cities or to neighbouring countries according to the fluctuations of the market and her disasters) – be it even only because of the cost (financial and human) of such a travel or the social and cultural selection inside of the family of those who can afford taking such a step.

If we try to understand everything that forms and traverses every individual rather than setting down the difference and otherness in order to justify an exterior position of ‘support’, we can view a whole complexity including the class differences. At that point we can determine that the collectives of paperless do as well exist out of over certified graduates, failed politicians, local exploiters who managed their travelling money on the expense of others… who migrate to this side of the world because they want to take their enjoyable place inside of the capitalist democracy. Thus many groups of paperless are being dominated by those who were already powerful (be it on a social, political or symbolical level) or were striving for it. These class differences are seldomly taken into account by comrades engaged in a struggle together with paperless people, a struggle in which language becomes an unavoidable and invisible barrier assigning the immigrants coming from the richer classes of their country automatically to the role of spokesman and translator. Sharpening these class differences as we do everywhere is not simply a contribution which can be made by comrades but a necessary condition for real solidarity.

In order to understand these struggle dynamics, throwing some comfortable illusions into the garbage bin is necessary as well. Only a stubborn determinism can claim that a certain social condition necessarily implicates the revolt against it. This kind of reasoning used to offer the guarantee of a revolution, a guarantee that many have cherished for a long time while simultaneously degrading the perspective of the individual rebellion which generalizes into insurrection to the level of an adventure. The criticism made on a determinism that has shown its failure in the old workers movement is suitable as well for the proletarians which migrate to this side of the world. Many amongst them look at the West as some kind of oasis where you can live nicely as long as you’re prepared to make big efforts. Undergoing conditions of exploitation that resemble what they’ve been running away from, with bosses who as well play on the paternalistic snare of belonging to a so called common community; being chased; not having any or only a few perspectives on climbing higher on the social ladder and a daily racism which tries to canalize the dissatisfaction of the other exploited, all of this makes up a rude reality to confront. Contrasting the resignation which can sprout from this painful confrontation or the reflex of locking oneself up into the authoritarian communities which are based on for example religion or nationalism, we put forward the perspective not to link up with all paperless in a ‘categorical’ way but with those who refuse their role as exploited and by this way open as well the identification of the enemy. We don’t want the blaming between the capitalist universality and the particularities but a social war in which we can recognize each other beyond the question of papers and different degrees of exploitation, in a permanent struggle for a society free of masters and slaves. As in any struggle in fact, would it not be that the struggle around migration mostly ends by the weight of the affective feeling of guilt, the urgency to prevent a deportation and its possible consequences, and all of this mostly via a relation based on exteriority instead of on a shared revolt.

The impasse of the struggle for regularisation

In several European countries, a lot of ‘massive’ regularisations took place at the last turn of the century. Although the State follows her own logic, the struggling paperless were able to influence the criteria and rhythm of the regularisations. A comparison can be made to all “big social reforms”, some of which have been achieved through bloodshed while others were buy-outs to maintain the social peace or simply granted in function of capitals need to keep the working class grouped and to increase interior consumption. In those days debates about demands that suit the capitals movement in contrast to insurrectional try-outs were going on in the working class as well. A lot of revolutionaries only accepted these demands as a possibility towards permanent agitation while at the same time it was clearly put that the social question could not be solved inside of a capitalist framework.

In the time preceding to these regularisation waves the States were divided between two adversary logics: the growing stream of clandestine migration did on the one hand fit the economic need for flexible workers (as in the construction, catering industry, cleaning sector, agriculture) of countries with an ageing population, on the other hand did this partly denied (as in countries knowing a more recent migration as Spain and Italy) but especially in nature less controllable population disturb the drastic will to manage the public order. While this issue was quickly resolved – more specifically by a closer cooperation between the different authorities (through the exchange of services between the imams and police offices as well as through the distribution of tasks amongst the different foreign and autochthonous mobs, despite some previous bloody games which had to do with unavoidable concurrence) -, the issue of the need for workers was resolved by a tighter interdependence between migration streams and the labour market. It seems to be one of the ruling tendencies on a European level to aim at a more worked out migration management which is tuned up in real time to the needs of the exploitation. Next to the classic labour form of the migrants (work in black) stands the migration which links the permit to stay to a working contract which will become the rule overtime, fitting the reorganisation of the labour delicacy which extends to everybody.

The state has almost put an end to the political asylum, has tightened up the family reunion and the obtainment of citizenship by marriage, has abolished the permit to stay for a longer period (like the one of 10 years in France), while she’s on the other hand rejecting regularisation demands using an iron fist. The state directs itself towards what was called “chosen migration” by a certain president. We’re returning to the era in which the sergeant recruiters went to the villages and loaded trucks with the amount of migrants needed by their bosses. The modern formula simply asks a rationalisation of this recruitment on the borders, co managed by the state and the employers (2). The workers are absolutely not supposed to stay and settle down. At the same time different camps at the external borders of Europe are under construction by the state, camps for those who have not been chosen by the grace of the slave tradesmen.

Because all the others are there. All those standing in front of a closed gate and all those continuing to arrive. That’s what’s at stake for the change in the degree of the police rationalisation of the deportation system which continues multiplying its camps and organizes more and more massive deportations, national quotes and European charter flights for those who managed their way through the locks of the waiting zones and the racketeering of the human traffickers and other mobs. However nobody cherishes any real illusions: the number of migrants without papers will increase as long as the economic causes continue to exist no matter what deployment (as can be seen at the border between Mexico and the States where a wall of 1200 kilometres is under construction), which will have no consequences apart from the increase of the passage costs and the amount of dead. Only the multiplication of her deportations would enable the state to apply her laws concerning forced expulsion from the territory. But that is not the question, because these deployments do not primarily aim at deporting all paperless, but serve to terrorize the whole of the immigrated workers (the regularized as well as those chosen to have a permit to stay) so that their condition of exploitation which resembles the one they escaped can remain unaltered (internal delocalisation in a certain way) while pressure is put down on the whole of the exploitation conditions. The racist excuse moreover serves to deploy the arsenal of social control which touches everybody.

But let us neither forget about the changing character of migration itself. Industrial capitalism used workers as pawns on a game board following an easy logic: here we have too many workers and there we need them. And whenever the need was rather small, other aspects of this population politics were put into action. However, this specific form of migration control has changed as a result of the restructuring of the economic aspect and because of the consequences of industrial growth. You can notice that speaking of a point of departure as well as a point of arrival becomes more difficult. The points of department have been devastated by hunger, war and disasters while the destinations are changing all the time. In this way migration becomes an endless track consisting of different stages; it’s no longer a movement from point A to B. These new forms of migration are not only being defined by the needs of a constantly flexible and adjustable capital. Millions of people, uprooted by the devastation of the places where they were been born are swarming all over this world – ready to be put at work. And the deployments of this control are very visible: the humanitarian refugee camps, the camps at the borders, the slums and the favelas. The struggles for regularisation seem to pose rather few questions concerning this new fact. The situation in Belgium is a good example of the current impasses of the struggle for regularisation. The state acted simultaneously as a lion and a fox when the tension around the closed centres began to rise in 1998. As a lion she repressed the most rebellious parts of the movement (murder of Semira Adamu (3) who was resisting stiffly in the centres; house searches and arrest of comrades who were active in this struggle). As a fox she started negotiating about regularisations with the other part of the movement. Clearly, the demand for regularisation (besides the fact that it equals the demand for integration) does require certain credibility, a recognized mediator. The movement got hit in this way. Regularisation, which once used to be the answer of the state to the tension and agitation which challenged the whole of the migration politics (using slogans against all camps or for a free circulation), became the goal for most of the paperless groups. Instead of forcing the state to give a bonus by struggling, the collectives started a dialogue which was followed by negotiations which attracted a whole army of professional negotiators and juridical charlatans who would solve all problems. The dynamics were on the one hand broken by repression and on the other hand by the start of a bureaucratic dialogue. Neither the successive self-mutilations (as the hunger strikes outside of the camps), nor the most servile self-abasements were enough to win what in a certain way used to be an answer of the state on agitation. The first answer of the state was combined with a rationalisation of the closed centres and a stricter adjustment of the permits to stay in connection to the needs of the economy (the state herself gave different colours to the cards).

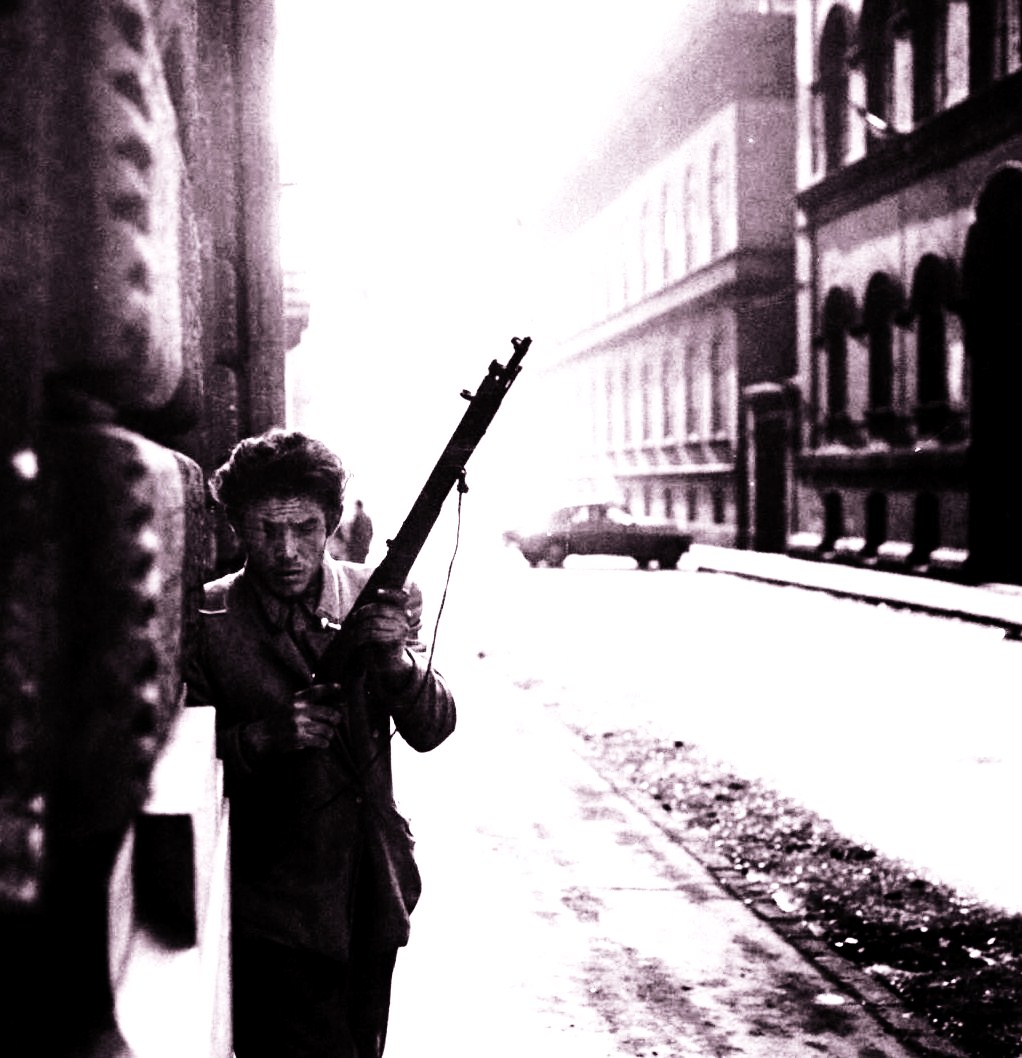

During the last years the current situation with its cycle of occupations/hunger strikes/deportations suffocated us during the last years in a struggle experience which offered only a few possibilities to go beyond and share a perspective: experiences of self organisation which do not accept neither politician nor religious or trade union leaders; direct actions which permit the development of a real power balance and the identification of the class enemy in all of her aspects. These observations lead us to feel the need and desire for developing a subversive projectuality departing from our bases, instead of running behind an enlargement (which seems to be more and more further away) based on the demand for regularisation. This projectuality could find her first anchors in the revolt which is factually shared amongst those who struggle for the destruction of the centres and those who (e.g. the rebels of Vincennes or Steenokkerzeel) put the critic of detention into deeds by putting their prison on fire.

Against the deportation machine

While facing these difficulties a debate that is still going on nowadays rises: the debate about solidarity. A lot of comrades continue defending the necessity –at whatever cost- of our presence inside of the paperless groups, until they retreat from any similar struggle, disgusted after so many blows. The justifications are diverse and most of the time a reflection of an activism or of comfortable recipes lacking imagination, lacking any real desire for subversion. And here as well: although the collective character of an action is no criterion for us, we do understand the need “to break the isolation” felt by some comrades. Nevertheless do we doubt if we can manage this by participating in endless meetings, being locked up with 30 people in a squat or an apartment block of paperless and leftists. We tend more towards the development of our own project and so to start from our own bases. As long as solidarity is understood as support to certain social categories, it will continue being an illusion. Even if it would entail some more radical methods, it will continuously be dragged along in a conflict with bases, methods and perspectives which are not ours at all. The only justification left is claiming that by taking part in these conflicts we can ‘radicalize’ the people because their social condition would necessarily lead them towards sharing our ideas. As long as this concept of ‘radicalisation’ is understood as a task of missionaries wanting others to swallow their ideas it will continue to be stuck in the impasse which we notice growing everywhere around. This ‘radicalisation’ however can as well be understood as openness of our dynamic towards others, enabling us to guarantee the autonomy of our own projectuality. In this way, ‘being together’ in a struggle and going forward on the level of perspectives as well as methods demands an existing basic affinity, a first rupture, a first desire that goes beyond the usual demands. In this way our demand for mutuality can become meaningful. There are a lot more tracks to explore than the continuation of the connection which only reason for existing is the maintenance of the fiction of the political subject that in the name of its statute as being the main victim, monopolizes the reason for the struggle and by this way the struggle itself. To put things clear we could say that solidarity is in need of a mutual recognition in deeds as well as in words. It is difficult to be solidary with a paperless “in struggle” who demands his regularisation and the one of his family without any interest whatsoever in the perspective of the destruction of the closed centres. Maybe we would still meet somewhere but this will be on a purely practical base: we don’t need to analyse the reasons nor perspectives which bring somebody to revolt in order to recognize ourselves, at least partly, in these deeds of attack which automatically turn against the responsibles of this misery. As counts for most of the intermediary struggles: there is only a very limited sense in participating to a factory conflict which departs from demands for wage and does not overcome the trade unionist framework, nor develops any sign of direct action. It is limited because there simply is no common base. New perspectives open up at the moment when these workers start sabotaging (even if they regard it as a means to pressure the bosses) or kick out their deputes (even if only because they feel betrayed).

So, instead of holding on to more and more slogans such as “solidarity with the immigrants / in struggle” (but which struggle?), we could develop a projectuality against the closed centres using methods and ideas which are ours and subversive in the sense that they question the foundations of this world (the exploitation and domination). This projectuality would be autonomous and strengthened by deeds of revolt contrasting the overall resignation, and strengthening these deeds in return. Again, recipes do not exist but today it is important to go beyond the impasses of a more or less humanist activism which hinders any radical autonomy in favour of an agitation which conceives the cadence of power or follows the logic of the only as legitimate conceived actors of the struggle, while it is actually the freedom of all which is at stake as for example in the case of the raids. As it is important to put forward perspectives which, beyond the partial goals developed in these intermediary struggles, are able to widen up the matter to a horizon which finally questions the whole of this world and its horror; meaning perspectives which are able to always put forward the matters of domination and exploitation. The diffuse attacks could make up the heart of this projectuality. Not only do they offer the advantage of exceeding the powerlessness felt while standing in front of the wall or barbed wire of a camp or while being confronted to a raid with a police deployment that can adjust itself and count on the passivity and fear of the passer-bys, but as well and especially do they offer us on the one hand the possibility to develop our own temporality and on the other hand to show everyone that the structures of the deportation machine which can be found on every corner of the street are vulnerable and at last they offer real action possibilities to everyone, regardless of the number they are.

/Some enthusiastic Internationalists

http://acorpsperdu.wikidot.com/touching-the-heart

![Eurorepressione - Sulla conferenza a Den Haag sul tema "Anarchia" [corretto]](http://25.media.tumblr.com/tumblr_m0jvngOXtY1qa2163o1_1280.jpg)

![A tres años de la Partida de Mauricio Morales: De la Memoria a la Calle [Stgo.]](http://metiendoruido.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/mmacividad.jpg)

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento