People on the left consider the anti-authoritarian movement, and especially the anarchists, as something that is childish or just imitating the west, the creation of people that do not yet understand their own identity. Their reasoning is straightforward, because there is no anti-authoritarian history in Indonesia. Indonesian society, we are told, is a feudal society that is not capable of acting without a command structure and an elite leadership; the actions that are glorified by adherents of anti-authoritarianism always refer to Western states. That’s because, they say, anti-authoritarianism and anarchism are absolutely irrelevant in the Indonesian context.

But let’s take a look just how these people on the left have only one talent: to lie.

Just as this world is the logical consequence of the accumulation of power in the hands of a select elite, so will it reap a ripe harvest of resistance everywhere and in many different forms. Of all this resistance, only a small amount is known about, mainly because dominant power is organised so that all resistance will be forgotten by history and wiped from the memories of the people. If there is something that is permitted to stay remembered, the design is such that it is only to be remembered for its failings, not for its victories.

Various media discuss popular uprisings and resistance in different areas, but without really giving much true understanding. ‘Militant’ media such as Rumah Kiri which is nowadays dominated by trotskyists actually occasionally publishes well-documented articles about the worker’s resistance that takes place directly despite all attempts to organise labour, such as that written by the Perhimpunan Rakyat Pekerja (PRP). But also unwittingly, by placing these next to other articles that are orientated towards power and the stability of the system, this becomes one more way to reintegrate those workers into the social order once more. In the same way that the binary opposites of the old world prove once more their ineffectiveness – or even intentionally fail to get to grips with the poverty of life at the most fundamental level – and what happens instead is that aspirations for a free life are buried.

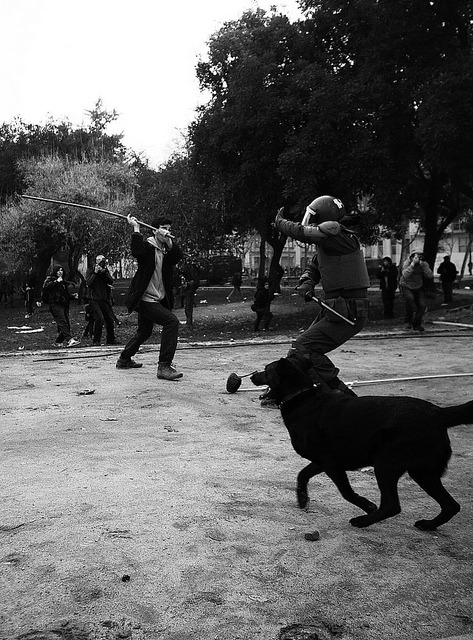

In the informal organisations of classic resistance, in the early days of Indonesian independence, many “criminal” actions took place, which also formed a critique of centralised power. Similarly, nowadays, we see many actions which not infrequently bear the scent of violence, that are also often labelled as ‘criminal acts’. In both the above cases the significant thing is not their criminality nor their violence, it is the rebellion that has the potential to build up the positive hopes of those that crave a life that can be lived more fully. Purging the influence of the historical experts and professionals of social science, we can highlight a few examples of actions that simply cannot fit within the pigeonhole of standard protest actions: such actions as those marches with people clinging on to their banners and placards, walking to a government building, shouting with a megaphone, negotiating with representatives of power. And then going back home again, accompanied by the chant “we’ll be back again with even greater numbers!”.

Around 1945 in the area of Brebes-Tegal-Pemalang (Central Java) poor farmers, feeling let down and angry, urged on by local criminal personalities, started to attack the rural elite, shaming the nobility and in several cases killing them. When some of their prominent members were arrested by TKR (Indonesian military that the newly independent central government approved of), they formed their own commandos with the aim of freeing their friends. In the end they were destroyed by the military allied with moderate Islamic groups that were dominated by the middle class. Of those imprisoned, some were sentenced to death. The almost spontaneous explosion of action, although not well-organised, was nevertheless a rebellion that not only fought physical poverty, but also the poverty of living, and also showed how the central government power was irrelevant to the actual needs of the local people.

Several decades later in North Sumatra, in a place known as Porsea, a paper factory was forced to its knees thanks to the unabating wave of action set in motion by the local people. This popular action was not commanded by intellectuals, movement leaders or political activists, and truly involved all layers of society including mothers and their children, making blockades, that sometimes were sometimes merely their own bodies, facing down the company’s trucks. There were no moderate demands such as for nationalisation of the factory, they only desired one thing: that there would be no factory near to their homes. After the fall of Suharto and the talk of a ‘democratic era’, the factory started to operate again, but the people were not as militant as before. What had happened was that certain figures of the LSM and activist movement that had sprung up had managed to make the community of Porsea understand how to carry out ‘civil protests suitable for a democratic environment’. The result was that the factory could operate smoothly while the people’s representatives wasted time at the diplomatic table with no conclusion. The actions of the people of Porsea only show one thing, that only direct action brings results, not the democratic diplomacy supported by intellectuals.

In 2001 the government gave notice of a new labour law that would force the workers into a corner, as part of its efforts to ensure the ‘health’ of the national economy. Ignored by the intellectuals who were busy debating on television without producing any result, workers in Bandung went on strike. Regardless of whether or not they had the approval of the trade union in each factory, the workers took to the streets. Without many banners, flags or megaphones, when they came to the government buildings they didn’t negotiate but instead started hurling stones at the building, and overturning and burning cars that were parked in the building’s compound. When the police arrived firing tear gas, the angry workers would disperse. But they wouldn’t return home quietly however, they regrouped in small groups with no central command, leaving the government building to break shop windows and damage expensive cars along the routes they followed. On the second day, transport workers responded to the workers’ action by carrying out a mass strike. Any public transport vehicle that did not join the strike was held up and bombarded with stones by the strikers. Beset by the violent action of workers and the lack of public transport, the production and transportation of capital was forced to a halt. On the third day, the army was sent to transport terminals and forced the drivers to resume the service. Factories that had been meeting places for the workers were visited and the workers forced back to work. The movement leaders were arrested . A shocked media, before they really had a chance to think about it, spontaneously aired the news across the nation, which only helped to provoke similar actions in various other places. As workers’ revolts erupted in various cities without being able to be extinguished, the government let it be known that the new law would be cancelled.

In 2002 the government announced a rise in fuel prices and a fuel truck was sequestered by a group of students who made it known that they were going to hold the on their campus as a symbolic protest. But in the small city of Cimahi, a criminal motorbike gang arrived at a petrol station, and forced the workers to fill their tanks for free, threatening violence if they didn’t. As other people around were shocked by this sudden action, the gang members encouraged them all to fill their tanks for free under the gang’s protection. In a moment, the local people flooded the petrol station and took the fuel with nothing to stop them. Not long afterwards the gang left the pumps and dispersed, as did the local people. The police that arrived were not able to arrest anyone since everyone around had participated in the plunder. What can be indirectly taken from this event is how the action of one group finds its own way to link in with a wider social environment. In the eyes of the local people, there was nothing to condemn about a motorbike gang hijacking a petrol station.

At the beginning of 2009, a medium-sized cargo ship was sailing the Java Sea when it suddenly changed it’s course and started sailing towards the borders of Indonesia. An upheaval had occurred inside the ship. Originating from a loathing of the captain who always forced the crew to work harder than their physical limits could support, it reached it’s peak when the ship’s cook attacked the captain with a kitchen knife. The captain’s cries for help were responded to by the crew who instead of helping captured the captain and then threw him overboard with no life-jacket. Shocked at their own spontaneous action, they did not choose anyone to replace the captain. Together they decided to make decisions by consensus, as a replacement for the system where one decisions would be taken based on the wishes of only one leader. So the ship started to move away from Indonesian territory, when an Indonesian navy vessel intercepted them at the border of the Malacca Straits. The interesting point about this case is how consensus decision making comes about spontaneously without being aware that that is exactly the most revolutionary thing that the crew could do at that point, after they had effectively got rid of the dominant power.

Each of these cases, whether the assassination of nobility, blockading actions without compromise or the wish to be pacified, the violent action of factory workers , the holding-up of a petrol station and the takeover of a ship, can of course be regarded as a criminal action that disobeys the law, if it is removed from its actual context. But in each case, if we look a little deeper, we can also see the process of deconstruction of values. What was previously considered the right thing to do, actually does not take the side of the people and their everyday lives. When looked at in terms of morality and of right and wrong, are not all the above cases not simply responses to other actions which are far more clearly wrong, and because of that more immoral?

Providing a clear context for how to escape from the shackles of moral values and popular opinion about right and wrong is obviously something very important. Because of this it is something that will be resisted by the power elite or the established intellectual class, ie. the status quo. The measns they will use are by manipulating symbols and portraying all these actions as criminal acts, violations of the law that can only lead to more widespread chaos. Successful attempts at criminalisation are usually supported by those who take the role of intellectual figures such as experts in social studies, movement leaders, NGO campaigners, and the media, who all try to sever each action from its social context and instead shoehorn it into a choice of right or wrong, legal or illegal, violent or non-violent. The first step is always so, an attempt to make the public respond with antipathy. The next step is also significant, erasing it from history, or written history at least.

The powerful always try to remove from official history every action that does not have their blessing. Official history is history that only the winner writes. There is no place for those that lose, and if there is then it is only the story of how their failures; their successes, although they may be as minute as a drop of morning dew, are not highlighted. The lack of adequate history from the past shapes ways of thinking and methods of control in the present. An example, indeed the most striking example, is the absence of official history as taught in schools regarding human life before the birth of power into the hands of a small elite, about life in the old times when humans were fairly egalitarian with no government, specialists, army or police. This understanding eventually brings a sense of pessimism that reaches across modern society, especially in our surroundings, a pessimism about the possibility for a life that is egalitarian without the need for government, police or specialists to exist. It is unsurprising if the usual response when people hear anarchists’ proposals for a society without government is: “Is there is no government, how will we be able to live properly?”, or the more sarcastic comment “If there are no police, surely people will kill each other in the streets?”. These questions really are an expression of the result of the systematic erasing of history.

We could venture another question, about why protests nowadays are never more than a demonstration of people walking towards some government building, and culminating in some diplomatic negotiations that have never ever brought any results wherever they have arisen, other than maintaining the status quo. From the various responses we hear to this question, there is always some connection with the poverty of history: because there is no reference point for any other forms of protest that have ever taken place in this country. The post-independence history books only make note of the student protests in the 1960s – where not long afterwards the student leaders underwent a transformation and became part of the political elite. Therefore, in the mind of the public, this is one form of protest that can be carried out, because from what they see there have never actually been other forms of protest.

There is no path that can be better believed, or better understood, other than asserting our identity and the steps forward we take today by taking our references from those who have been in similar positions in the past. An understanding of the past tells us about who we are, and the choices of our predecessors, and also has relevance in drawing the map of the terrain on which we will play in the future. Exploring the past, without becoming trapped in it or idealising events that have happened in previous times, actually can make our present situation more concrete. We feel the connection more strongly and we become aware of the alienation that lurks in the places we dwell. To do this, we need to be able to find our lost history (or purposefully lost history), and evaluate it once again from our own points of view. In this way we can get a complete picture of our lives, an individual resurgence that resounds with the rhythm of the social need to discover the totality.

The history that is not included in the official historical dictionary is a tool we can use to build the structures for social war. Its documents can be found in unusual places, in the songs and stories of the people, or in oral history that has never been written down. Oral history especially is a different method of history, as it is more egalitarian. As Kuntowijoyo once said, oral history actually contributes a great deal to the development of the substance of history. Firstly, because of its contemporary character, oral history presents almost unlimited possibilities for unearthing history directly from those who made it. Secondly, oral history can include historical actors that official history leaves disregarded. This is because it is not an elitist image of reality: each and every person can become one of history’s figureheads. Thirdly, oral history makes possible an expansion of the scope of history, because history is not limited to that for which written documents exist. Now all that remains is for us to rediscover it within our own surroundings.

To define the poverty of our own lives, there must really also be a redefinition of what prosperity means. To redefine the shape of protest is also to redefine the meaning of right and wrong in our own lives, and of ideas about what is suitable for us to struggle against. No more is there a standard format that we should follow, no longer are there limits to a blueprint that has been given to us by movement figureheads that only see one possibility, no longer are possibilities closed off due to pessimism. Poor farmers of Mexico re-found their roots through a rediscovery of the meaning of the struggle of Emiliano Zapata at the start of the 20th century and transformed it into the Zapatista movement – maybe this is a wake-up call to remind us, not to become followers or idolizers of the Zapatistas, but to start rediscovering our own routes, on our own land, in order to find the successful methods for our own struggles.

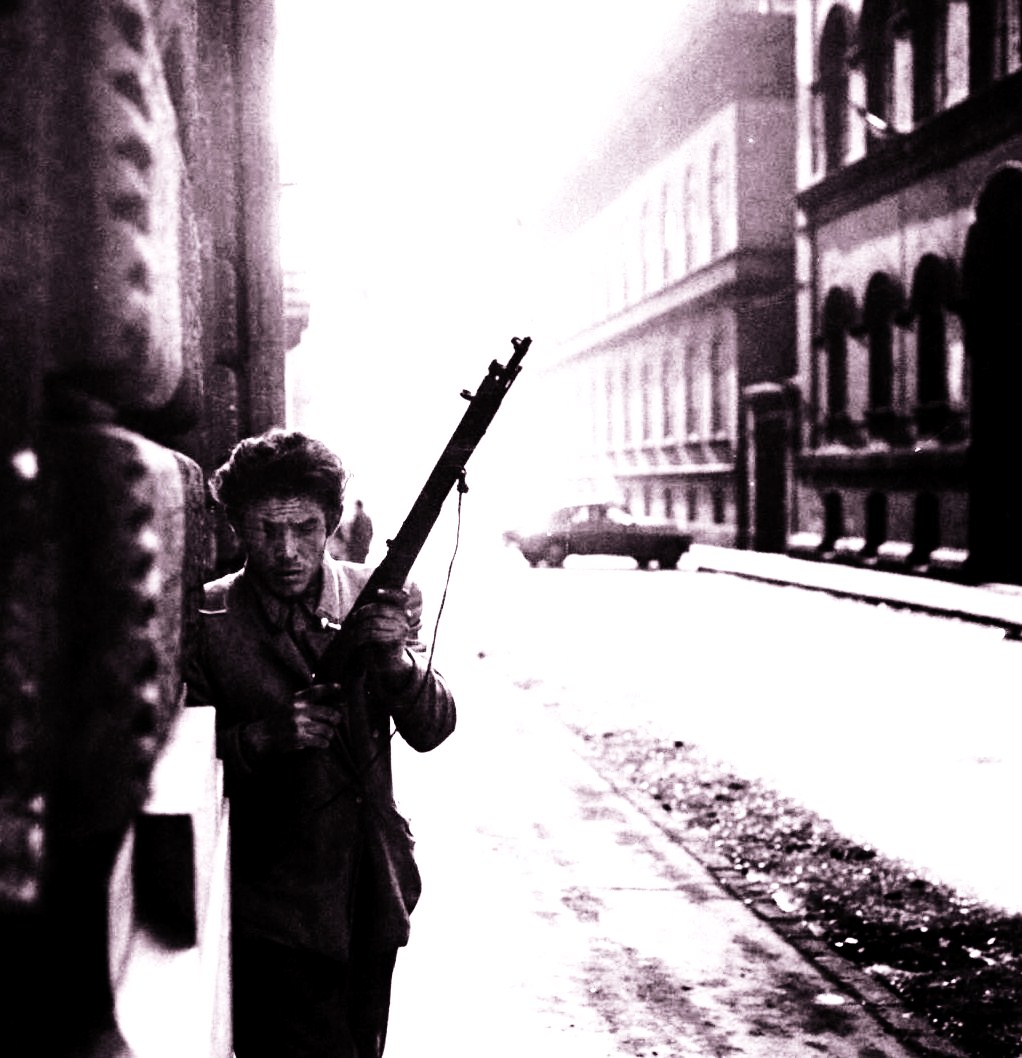

Forget Spain 1936. Forget Budapest 1956. Paris 1968. Greece 2008. Let’s fight on our own land. Right now.

-translated from Amor Fati magazine number 4. Original title “Menakar Tanah di Negeri Sendiri dan Menggali Harapan”

![Eurorepressione - Sulla conferenza a Den Haag sul tema "Anarchia" [corretto]](http://25.media.tumblr.com/tumblr_m0jvngOXtY1qa2163o1_1280.jpg)

![A tres años de la Partida de Mauricio Morales: De la Memoria a la Calle [Stgo.]](http://metiendoruido.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/mmacividad.jpg)

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento