Otto Gross, 18771920

Biographical Survey 1

http://www.ottogross.org/english/documents/BiographicalSurvey.html#Notes

by Gottfried Heuer

In telling the story of Gross' known life, Hurwitz' (1979) and Green's (1974, 1986, 1998) works have been most valuable.

Otto Hans Adolf Gross (also Grob) was born 17 March 1877 in Gniebing near Feldbach in Styria, Austria. His father Hans (or Hanns) Gross was a professor of criminality and one of the leading authorities worldwide in this field. (He is, for example, seen as the originator of dactyloscopy, the science of interpreting and using finger prints.)

Gross was mostly educated by private tutors and in private schools. He became a medical doctor in 1899 and travelled as a naval doctor to South America in 1900 at which time he became addicted to drugs. In 190102 he worked as a psychiatrist and assistant doctor in Munich and Graz, published his first papers and had his first treatment for drug addiction at the Burghölzli Clinic near Zürich. His initial contact with Freud was either at this time or by 1904 at the latest. The writer Franz Jung (no relation to C.G. Jung) claims that Gross became Freud's assistant much earlier than that but there is no evidence that Gross had any contact with Freud before 1904 other than his (F. Jung, 1923, P. 21) (2), except for a passage in a letter to Freud from C.G. Jung after his treatment of Gross, "I wish Gross could go back to you, this time as a patient" (Freud / Jung Letters, p. 161; my emphasis).

http://www.ottogross.org/english/documents/BiographicalSurvey.html#Notes

In 1903 he married Frieda Schloffer and was offered a chair in psychopathology at Graz university in 1906. The following year his son Peter was born as well as a second son, also named Peter, from his relationship with Else Jaffé, born Else von Richthofen. In the same year Gross had an affair with Else's sister, Frieda Weekley, who later married D.H. Lawrence. By that time Gross lived in Munich and Ascona, Switzerland, where he had an important influence on many of the expressionist writers and artists such as Karl Otten and Franz Werfel as well as anarchists and political radicals, like Erich Mühsam, who later was the first to proclaim the republic during the Munich Revolution of 1919. In 1908 Gross had further treatment at the Burghölzli where he was analysed by C.G. Jung - and, in turn, analysed Jung. In the same year his daughter Camilla was born from his relationship to the Swiss writer Regina Ullmann, who later became a close friend of Rilke.

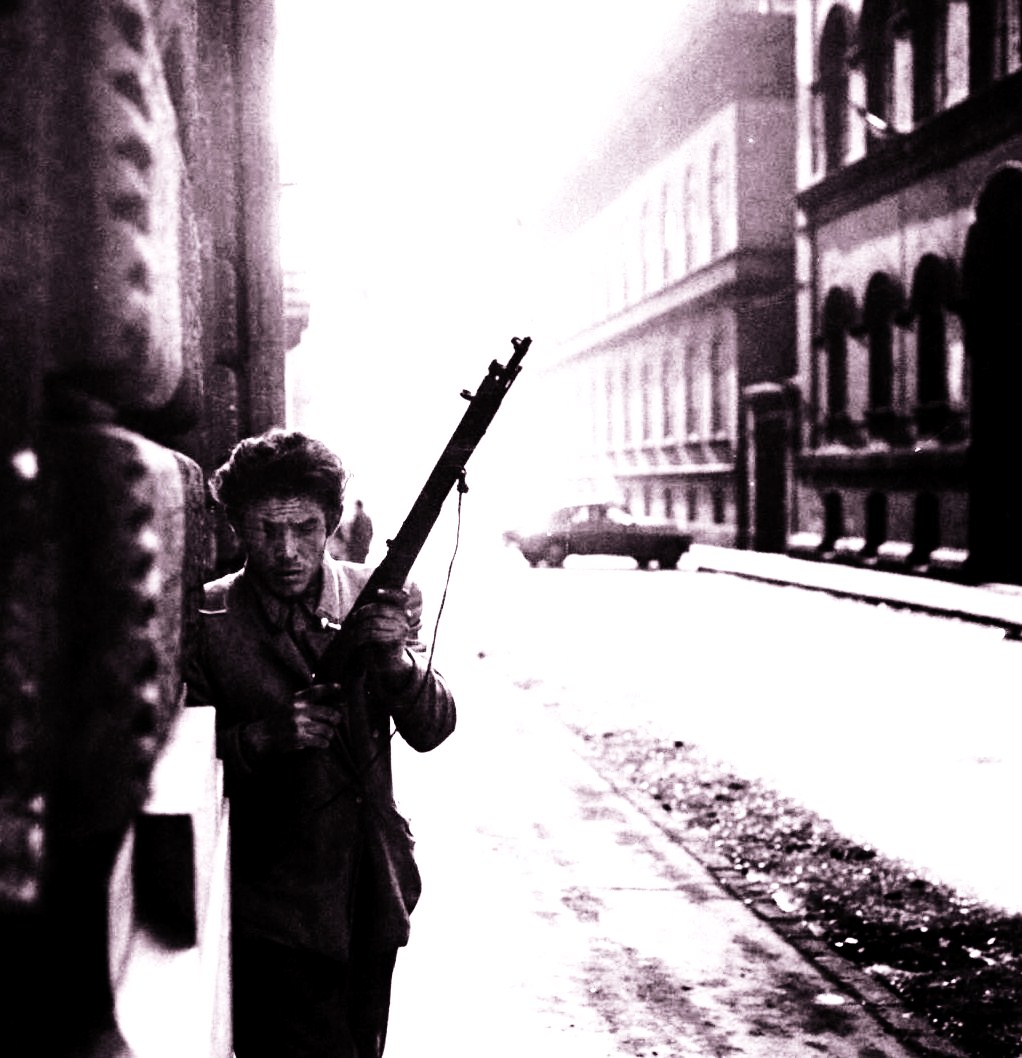

In 1911 Gross was forcibly interned in a psychiatric institution. He subsequently wanted to found a school for anarchists in Ascona and he wrote to the Swiss medical doctor and anarchist Fritz Brupbacher that he had plans to publish a "Journal on the psychological problems of anarchism". Two years later he lived in Berlin where he had a considerable influence on Franz Jung (the writer), Raoul Hausman, Hannah Höch and the other artists who created Berlin Dada. His father had Gross arrested as a dangerous anarchist and interned in a psychiatric institution in Austria. By the time he was freed following an international press campaign initiated by his friends, Gross had become one of the psychiatrists working at the hospital. Together with Franz Kafka Gross planned to publish "Blätter gegen den Machtwillen" (Journal Against the Will to Power). Legally declared to be of diminished responsibility, Gross was analyzed by Wilhelm Stekel in 1914 (cf. Stekel, 1925), declared cured but placed legally under the trusteeship of his father who died a year later, in 1915, when Gross was a military doctor first in Slavonia and then in Temesvar, Romania, where he was head of a typhus hospital. Together with Franz Jung, the painter Georg Schrimpf and others, Gross published a journal called "Die freie Strasse" (The Free Road) as a "preparatory work for the revolution". He began a relationship with Marianne Kuh, one of the sisters of the Austrian writer Anton Kuh, and in 1916 he had a daughter by her, Sophie. Because of his drug addiction, Gross was again put into a psychiatric institution under limited guardianship in 1917. He planned to marry Marianne, although he had a relationship not only with her sister, Nina, too, but, possibly, with the third sister, Margarethe, as well (Templer-Kuh, 1998). He died of pneumonia on 13 February 1920 in Berlin after having been found in the street near-starved and frozen. In one of the very few eulogies that were published, Otto Kaus wrote, "Germany's best revolutionary spirits have been educated and directly inspired by him. In a considerable number of powerful creations by the young generation one finds his ideas with that specific keenness and those far-reaching consequences that he was able to inspire" (1920, p. 55). Except for Wilhelm Stekel, who wrote a brief eulogy, published in New York (Stekel, 1920), but who was a psychoanalytic outcast himself by that time, and a mere announcement of Gross' death by Ernest Jones at the Eighth International Psycho-Analytical Congress in Salzburg four years later, the analytic world remained silent, a silence that has, with very few exceptions, effectively lasted to this day.

Theoretical Survey

What were the ideas Otto Gross contributed to the development of analytical theory and practice and what was it about them - and himself - that finally made him persona non grata - or an "non-person", to use the Stalinist term?

His personal experience of what appears to have been an overpowering father and a subservient mother, early on provided Gross with an experience of the roots of emotional suffering in relationships within a nuclear family structure. He wrote in favour of the freedom and equality of women and advocated free choice of partners and new forms of relationships which he envisaged as free from the use of force and violence. He made links between these issues and the hierarchical structures within the wider context of society and came to regard individual suffering as inseparable from that of all humanity: "The psychoanalyst's consulting room contains all of humanity's suffering from itself" (Gross, 1914, p. 529).

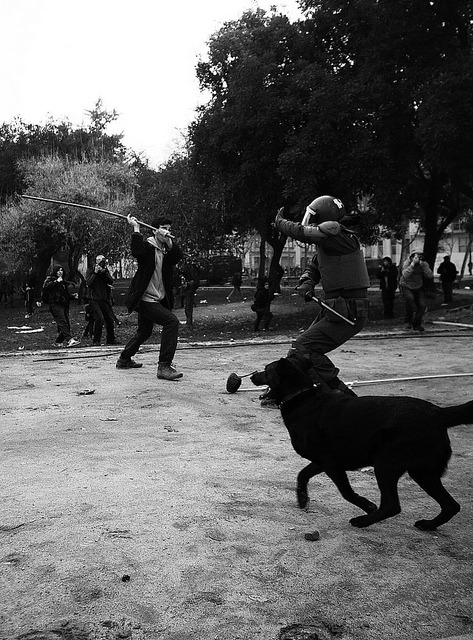

In his struggle against patriarchy in all its manifestations, Gross was fascinated by the ideas of Bachofen and others on matriarchy. "The coming revolution is a revolution for the mother-right," he wrote in 1913 (Gross, 1913a, Col. 387). He focussed on sexuality, yet soon came to question Freud's emphasis on it as the sole root of the neuroses. In contrast to Freud's view of the limits placed on human motivation by the unconscious, Gross saw pathologies as being rooted in more positive and creative tendencies in the unconscious. He wrote extensively about same-sex sexuality in both men and women and argued against its discrimination. For Gross, psychoanalysis was a weapon in a countercultural revolution to overthrow the existing order - not a means to force people to adapt better to it. He wrote, "The psychology of the unconscious is the philosophy of the revolution . . . It is called upon to enable an inner freedom, called upon as preparation for the revolution" (1913a, column 385, emphasis O.G.).

He saw body and mind as one, inseparable, writing that, "each psychical process is at the same time a physiological one" (Gross, 1907, p. 7). "Gross joins the ranks of those researchers who refute a division of the world into physical and spiritual-intellectual realms. For them body and soul are the expressions of one and the same process, and therefore a human being can only be seen holistically and as a whole" (Hurwitz, 1979, p. 66).

Nicolaus Sombart summarizes two main points. "His first thesis was: The realization of the anarchist alternative to the patriarchal order of society has to begin with the destruction of the latter. Without hesitation, Otto Gross owned up to practicing this -in accordance with anarchist principles - by the propaganda of the "example", first by an examplary way of life aimed at destroying the limitations of society within himself; second as a psychotherapist by trying to realize new forms of social life experimentally in founding unconventional relationships and communes (for example in Ascona from where he was expelled as an instigator of "orgies") . . . Gross was not homosexual but he saw bisexuality as a given and held that no man could know why he was loveable for a woman if he did not know about his own homosexual component. His respect of the sovereign freedom of human beings went so far that he did not only recognise their right for illness as an expression of a legitimate protest against a repressive society - here he is a forerunner of the Anti-Psychiatry of Ronald D. Laing and Alain Fourcade - but their death wishes as well, and as a physician he helped with the realization of those, too. He was prosecuted and incarcerated for assisting suicide.

His second thesis: Whoever wants to change the structures of power (and production) in a repressive society, has to start by changing these structures in himself and to eradicate the "authority that has infiltrated one's own inner being". In his opinion it is the achievement of psychoanalysis as a science to have created the preconditions and to have provided the instruments for this (Sombart, 1991, pp. 1l0f.).

Behind Gross' emphatic focus on transgression lies a profound realisation of the interconnectedness of everyone and everything. Therefore all boundaries may be seen as arbitrary and transgressing boundaries then becomes a protest against their unnaturalness. From a psychopathological perspective it would be all too facile to diagnose - not unreasonably, though - a father complex, an unresolved incestuous tie to the mother, a neurotic longing for paradise as a return to the womb etc., etc. Very similar diagnoses, incidentally, could easily be made of the other founding fathers of analysis. But this would mean that we remain in the compartmentalized realm of reason and rationality alone, where everything and everybody is separated from from everything and everybody else. The historiography of analysis will lose out if we were to brand Gross - as Jung and Freud did - a hopeless lunatic, or maybe a puer aeternus, nothing but a charismatic failure.

From a conceptual point of view, Gross' transgressions can be understood as a longing for transcendence - a transcendence via the body that does not leave the body behind in order to fly off into a purely spiritual, uncorporeal sphere. I see his work as an understanding of the ensoulment of matter and flesh. Analysts do not unsually write about ecstasy, lust, orgy. Those who did paid the price of becoming ostracized as outcasts - Gross, Reich, Laing. It is only comparatively recently that analytic authors have ventured as far as "the spontaneous gesture" (Winnicott, in Rodman, ed., 1987) or "acts of freedom" (Symington, 1990).

It seems that Otto Gross has remained largely unknown to this day because in true mercurial fashion he travelled deep into the underworld and high into the heavens, trying to hold together experiences of both realms. Freud, Jung and Reich all returned from their respective creative illnesses or night-sea journeys comparatively intact and lived to tell of them in a coherent manner. Gross did not.

With his advocacy of sex, drugs and anarchy, Gross corresponded to a spectre feared by the German-speaking bourgeoisie of Europe, a threat to values of family and state. My hypothesis is that Gross remained relatively unknown to this day because of his radical critique and his insistence that there is no individual change without collective change and vice versa. There is a temptation to romanticize Gross as a forgotten genius/martyr of the analytic movement. Ernest Jones, who had met Gross in Munich in 1908, where Gross introduced him to psychoanalysis, called him in his autobiography in the late forties "the nearest approach to the romantic ideal of a genius I have ever met" (Jones, 1990, p. 173). But to focus on this aspect alone would mean assessing Gross uncritically, overlooking his (self-)destructive side.

Notes

(1) The biographical and theoretical surveys are excerpts from Gottfried Heuer, Jung's Twin Brother. Otto Gross and Carl Gustav Jung. Gross' children and grandchildren. In: Association of Jungian Analysts, ed., Festschrift 1977 ©1998, London, 1998.

(2) All translations from titles quoted in German by G.H.

Bibliography

The Freud/Jung Letters. The Correspondence between Sigmund Freud and C. G. Jung. Ed. by William McGuire, translated by Ralph Mannheim and R.F.C. Hull. London: The Hogarth Press and Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1974.

Green, Martin. The von Richthofen Sisters. The Triumphant and the Tragic Mode of Love. Else and Frieda von Richthofen, Otto Gross, Max Weber, and D.H. Lawrence, in the Years 18701970. New York: Basic Books, 1974.

Green, Martin. Mountain of Truth. The Counterculture Begins. Ascona, 19001920. Hanover and London: University Press of New England,1986.

Green, Martin. New Age Messiah. The Life and Times of Otto Gross. Lewiston, N.Y.: Edwin Mellen Press, 1999 (in press).

Gross, Otto. Das Freudsche Ideogenitätsmoment und seine Bedeutung im manisch-depressiven Irresein Kraepelins. Leipzig: F.C.W. Vogel, 1907.

Gross, Otto. Zur Überwindung der kulturellen Krise, in Die Aktion, Nr. 14, III. Jahr, 2. April, 1913, Col. 384 - 387.

Gross, Otto. Über Destruktionssymbolik, in Zentralblatt für Psychoanalyse und Psychotherapie, Vol. IV, No. 11/12, 1914, pp. 525534.

Jones, Ernest. Free Associations. New Brunswick and London: Transaction, 1990.

Hurwitz, Emanuel. Otto Gross. Paradies-Sucher zwischen Freud und Jung. Zürich: Suhrkamp, 1979.

Jung, Franz. Von geschlechtlicher Not zur sozialen Katastrophe. Manuscript. Berlin: Cläre Jung Archiv of the Stiftung Archiv der Akademie der Künste, ca. 1923. (First published as an appendix in Michaels, 1983.)

K(aus)., O(tto). Mitteilungen, in Sowjet. Nr. 8/9, 8 May, 1920, pp. 5357.

Michaels, Jennifer E. Anarchy and Eros. Otto Gross' Impact on German Expressionist Writers: Leonhard Frank, Franz Jung, Johannes R. Becher, Karl Otten, Curth Corrinth, Walter Hasenclever, Oskar Maria Graf; Franz Kafka, Franz Werfel, Max Brod, Raoul Hausmann and Berlin Dada. New York: Peter Lang, 1983.

Rodman, F. Robert, ed. The Spontaneous Gesture. Selected Letters of D. W Winnicott. Cambridge, Ma., London: Harvard University Press, 1987.

Sombart, Nicolaus. Die deutschen Männer und ihre Feinde. Carl Schmitt - ein deutsches Schicksal zwischen Männerbund und Matriarchatsmythos. München, Wien: Carl Hanser, 1991.

Stekel, Wilhelm. In Memoriam, in Psyche and Eros, Vol. 1, 1920, p. 49.

Stekel, Wilhelm. Die Tragödie eines Analytikers, in Störungen des Trieb-und Affektlebens. (Die Parapathischen Erkrankungen). VIII. Sadismus und Masochismus. Berlin und Wien: Urban & Schwarzenberg, 1925, pp. 484511.

Symington, Neville. The possibility of human freedom and its transmission (with particular reference to the thought of Bion), in International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, Vol. 71, 1990, pp. 95106.

Templer-Kuh, Sophie. Personal Communication. 29 June,1998.

http://www.ottogross.org/english/documents/BiographicalSurvey.html

![Eurorepressione - Sulla conferenza a Den Haag sul tema "Anarchia" [corretto]](http://25.media.tumblr.com/tumblr_m0jvngOXtY1qa2163o1_1280.jpg)

![A tres años de la Partida de Mauricio Morales: De la Memoria a la Calle [Stgo.]](http://metiendoruido.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/mmacividad.jpg)

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento