by Dr. Steven Best (Introduction to Global Industrial Complex)

http://www.amazon.com/Global-Industrial-Complex-Systems-Domination/dp/0739136984/ref=sr_1_5?ie=UTF8&qid=1324155767&sr=8-5

Investigations of various topics and levels of abstraction that are collected here are united in the intention of developing a theory of the present society. —Max Horkheimer

Since trade ignores national boundaries and the manufacturer insists on having the world as a market, the flag of his nation must follow him, and the doors of the nations which are closed against him must be battered down. Concessions obtained by financiers must be safeguarded by ministers of state, even if the sovereignty of unwilling nations be outraged in the process. Colonies must be obtained or planted, in order that no useful corner of the world may be overlooked or left unused.—Woodrow Wilson, 1919

Globalization has considerably accelerated in recent years following the dizzying expansion of communications and transport and the equally stupefying transnational mergers of capital. We must not confuse globalization with “internationalism” though. We know that the human condition is universal, that we share similar passions, fears, needs and dreams, but this has nothing to do with the “rubbing out” of national borders as a result of unrestricted capital movements. One thing is the free movement of peoples, the other of money. —Eduardo Galeano

Matrices of Control:

Modernity, Industrialism, and Capitalism

In the transition to what is called “modernity”—a revolutionary European and American social order driven by markets, science, and technology—reason awakens to its potential power and embarks on the project to theoretically comprehend and to practically “master” the world. For modern science to develop, heretics had to disenchant the world and eradicate all views of nature as infused with living or spiritual forces. This required a frontal attack on the notion that the mind participates in the world, and the sublation of all manner of the animistic and religious ideologies—from the Pre-Socratics to Renaissance alchemists to indigenous cosmological systems—which believed that nature was magical, divine, or suffused with spirit and intelligence.[i]

This became possible only with the dethronement of God as the locus of knowledge and value, in favor of a secular outlook that exploited mathematics, physics, technology, and the experimental method to unlock the mysteries of the universe. Modern science began with the Copernican shift from a geocentric to a heliocentric universe in the sixteenth century, advanced in the seventeenth century with Galileo’s challenge to the hegemony of the Church and pioneering use of mechanics and measurement, while bolstered by Bacon and Descartes’ call to command and commandeer nature; and reached a high point with Newton’s discoveries of the laws of gravity, further inspiring a mechanistic worldview developed by Enlightenment thinkers during the eighteenth century.

For the major architects of the modern worldview—Galilee Galileo, Francis Bacon, Rene Descartes, and Isaac Newton—the cosmos is a vast machine governed by immutable laws which function in a stable and orderly way that can be discerned by the rational mind and manipulated for human benefit. Beginning in the sixteenth century, scientific explanations of the world replace theological explanations; knowledge is used no longer to serve God and shore up faith, but rather to serve the needs of human beings and to expand their power over nature. Where philosophers in the premodern world believed that the purpose of knowledge was to know God and to contemplate eternal truths, modernist exalted applied knowledge and demystified the purpose of knowledge as nothing more than to extend the “power and greatness of man” to command natural forces for “the relief of man’s estate.”[ii]

Through advancing mathematical and physical explanations of the universe, modernists replaced a qualitative, sacred definition of reality with a strictly quantitative hermeneutics that “disenchanted” (Berman)[iii] the world and ultimately presided over the “death of nature” (Merchant).[iv] This involved transforming the understanding of the universe as a living cosmos into a dead machine, thus removing any qualms scientists and technicians might have in the misguided project of “mastering” nature for human purposes.

The machine metaphor was apt, not only because of the spread of machines and factories throughout emerging capitalist society, but also because—representing something orderly, precise, determined, knowable, and controllable—it was the totem for European modernity. Newton’s discoveries of the laws of gravity vindicated the mechanistic worldview and scores of eighteenth and nineteenth century thinkers (such as Holbach and La Mettrie) set out to apply this materialist and determinist paradigm to the earth as well as to the heavens, on the assumption that similar laws, harmonies, and regularities governed society and human nature. Once the laws of history, social change, and human nature were grasped, the new “social scientists” speculated, human behavior and social dynamics could be similarly managed through application of the order, harmony, prediction, and control that allowed for the scientific governance of natural bodies.

The rationalization, quantification, and abstraction process generated by science, where the natural world was emptied of meaning and reduced to quantitative value, is paralleled in dynamics unleashed by capitalism, in which all things and beings are reduced to exchange value and the pursuit of profit. In both science and capitalism, an aggressive nihilism obliterates intrinsic value and reduces natural, biological, and social reality to instrumental value, viewing the entire world from the interest of dissection, manipulation, and exploitation. Science sharply separates “fact” from “value,” thereby pursuing a “neutral” or “objective” study of natural systems apart from politics, ethics, and metaphysics, as capitalism bifurcates the public and private sectors, disburdening private enterprise of any public or moral obligations.

The kind of rationality that drives the modern scientific, economic, and technological revolutions—instrumental or administrative reason (herrschaftwissen)—is only one kind of knowledge, knowledge for the sake of power, profit, and control.[v] Unlike the type of rationality that is critical, ethical, communicative, and dialogical in nature, the goal of instrumental reason is to order, categorize, control, exploit, appropriate, and commandeer the physical and living worlds as means toward designated ends. Accordingly, this general type of reason—a vivid example of what Nietzsche diagnoses as the Western “will to power”—dominates the outlook and schemes of scientists, technicians, capitalists, bureaucrats, war strategists, and social scientists. Instrumental knowledge is based on prediction and control, and it attains this goal by linking science to technology, by employing sophisticated mathematical methods of measurement, by frequently serving capitalist interests, and by abstracting itself from all other concerns, often disparaged as “nonscientific,” “subjective,” or inefficient.

The dark, ugly, bellicose, repressive, violent, and predatory underbelly of the “disinterested” pursuit of knowledge, of “reason,” and of “democracy,” “freedom,” and “rights” as well, has been described through a litany of ungainly sociological terms, including, but not limited to: secularization, rationalization, commodification, reification (“thingification”), industrialization, standardization, homogenization, bureaucratization, and globalization. Each term describes a different aspect of modernity—reduction of the universe to mathematical symbols and equations, the mass production of identical objects, the standardization of individuals into the molds of conformity, the evolution of capitalist power from its competitive to monopolist to transnational stages, or the political and legal state apparatus of “representative” or “parliamentary” democracies. Each dynamic is part of a comprehensive, aggressive, protean, and multidimensional system of power and domination, co-constituted by the three main engines incessantly propelling modern change: science, capitalism, and technology.[vi] In industrial capitalist societies, elites deploy mathematics, science, technology, bureaucracies, states, militaries, and instrumental reason to render the world as something abstract, functional, calculable, and controllable, while transforming any and all things and beings into commodities manufactured and sold for profit.

From Exploitation to Administration

Critical theorists and postmodernists resisted Marxist economic reductionism to work out the implications of Weber’s “iron cage of rationality” that tightly enveloped the modern world by the nineteenth century. A critical counter-enlightenment trajectory leads from Nietzsche to Weber to Georg Lukács through Frankfurt School theorists like Theodor Adorno, Max Horkheimer, Herbert Marcuse, and Jurgen Habermas, to postmodernists such as Michel Foucault and Jean Baudrillard. Although many relied on key Marxist categories, they sought a more complex concept of power and resistance than allowed by the economistic emphasis on capital, alienated labor, and class struggle. Where Marx equates power with exploitation, the capital-labor relation, the factory system, and centralized corporate-state power, modern and postmodern theorists of administrative rationality brought to light the autonomous role that knowledge, reason, politics, and technique serve in producing systems of domination and control.

See the rest of this entry…

http://www.negotiationisover.net/2011/12/18/pathologies-of-power-and-the-rise-of-the-global-industrial-complex/#more-5322

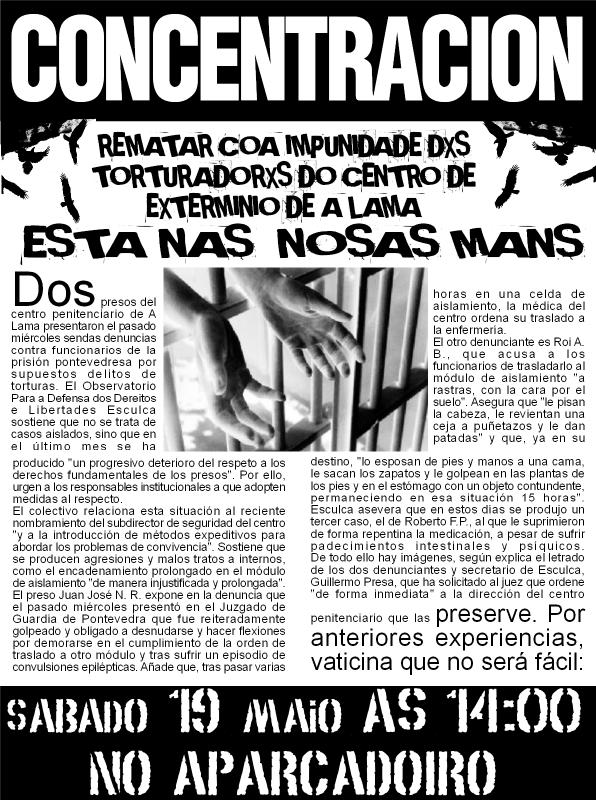

![Eurorepressione - Sulla conferenza a Den Haag sul tema "Anarchia" [corretto]](http://25.media.tumblr.com/tumblr_m0jvngOXtY1qa2163o1_1280.jpg)

![A tres años de la Partida de Mauricio Morales: De la Memoria a la Calle [Stgo.]](http://metiendoruido.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/mmacividad.jpg)

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento