Operation ‘Outlaw’ started on 6th April 2011 in Bologna (Italy) and led to the imprisonment of 6 comrades (one was released a few days later as the investigators couldn’t prove his involvement in an attack on ENI local premises), searches and restrictive measures on a number of others, and the closure of the anarchist place Fuoriluogo. After spending six months in detention between prison and house arrest, 5 comrades will face trial on 29th February 2012 along with another 22.

http://325.nostate.net/?p=2093

http://325.nostate.net/?tag=fuoriluogo

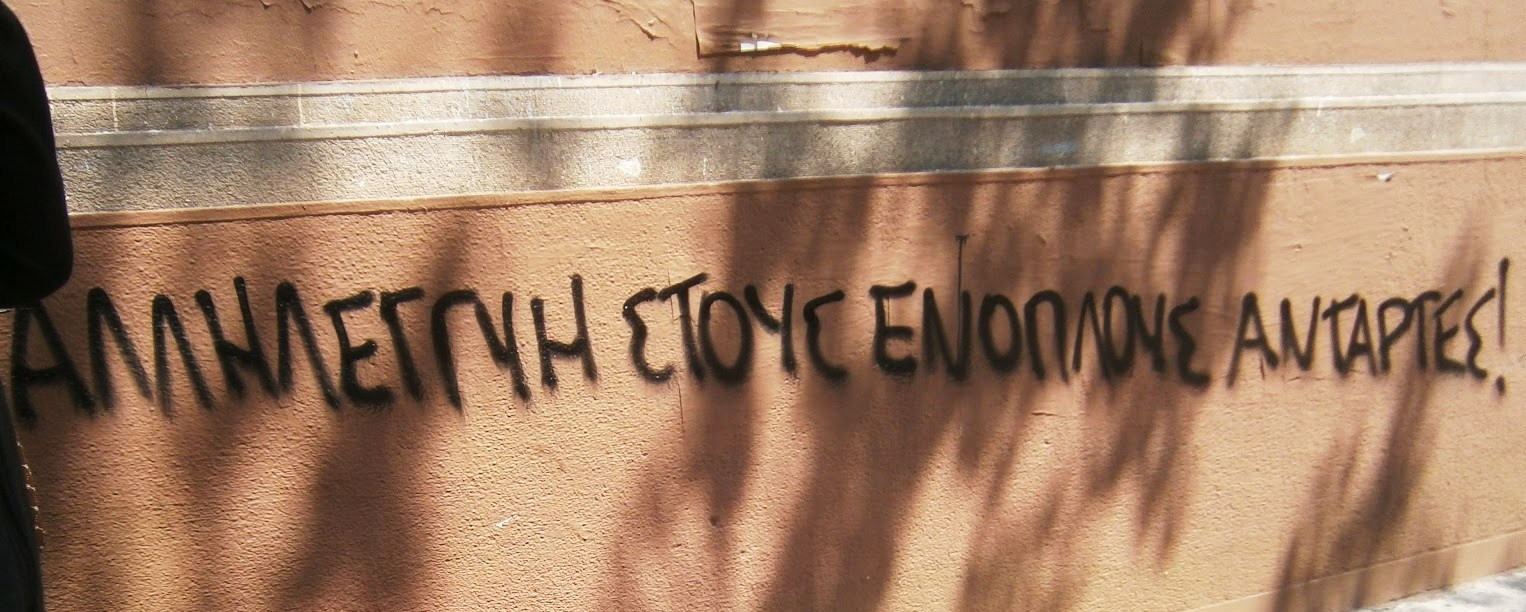

As exposed in the following articles, translated from ‘Invece’ (Issue 11, January 2012), the repressive situation in Bologna has become suffocating, to say the least, with police harassing the comrades every single day in all possible ways and also targeting whoever has any kind of relation with them. In addition to this, a strong denigrating press campaign against the Bologna anarchists is still being carried out in local and national newspapers, with the obvious intent of isolating the comrades and preventing any form of solidarity to them.

ENI, the Italian oil company, which the comrades have been denouncing and attacking for a long time, is one of the main protagonists behind this repressive apparatus. It has become evident how ENI dictates the editorial choices of some of the most important Italian dailies and weeklies, also with the complicity of the secret services. In fact, the connection between industrial lobbies, press agencies and military intelligence has always been a feature of social and political life in Italy. Not by chance the head of security of ENI, mentioned in the second article, is a former senior officer of SISMI (Italian secret service).

We do believe it is worth publishing these articles in English because the repressive assault on the Bologna anarchists concerns us all.

Solidarity in the attack knows no borders.

The Wild West

This story is set in Bologna, a traditionally bourgeois and leftist city. The environment is favourable to the demands of a cultural elite with radical chic attitudes. It is a wealthy city, for century dominated by the interests of a class of traders that dictates its own rules. From transport to city planning, from economy to public order management, pressures on the public administration are made by committees against urban degradation, lock-outs to impose the most advantageous conditions for shopkeepers, and opposition to traffic restrictions against pollution, to the point of claiming the ‘requalification’ of entire areas of the centre in order to liberate it from penniless and unwelcome inhabitants or frequenters.

A very important source of wealth comes from the most ancient university in the world, which attracts a huge number of students ready to pay a lot of money for rent, food and ‘entertainment’. They pay and contribute to raising prices, which are at the highest levels in the country. Your purse has to be full if you want to live in Bologna, and now there exist no free areas in this city where you can live with imagination.

On its part antagonism in Bologna goes side by side with public administrators, who decide how much space and grants can be conceded, according to the occasions and political interests. In exchange for premises and political agility antagonism moves through balancing acts in order to contain the intemperance inside it without loosing a facade of conflictuality, and when the occasion arises it takes distance from those it can’t control. In a transit place like Bologna activism qualifies itself as temporary attitude, generational and trendy, also considering the fixed-term engagement of those who live in this city for a few yeas and then go back to where they came from, like students from other towns or researchers who do their training here.

In a context like this one what is happening to a group of anarchists kept in check by police and magistrates, and which we are going to briefly expose, finds it very hard to encounter a fertile ground for solidarity.

For several years the Bologna Digos [political police] has been patrolling the city day and night with real dedication, chasing maniacally all those whom it has the order to keep under control. You can’t get out of your house without being stopped at least once a day and these ‘normal police checks’ are subsequently marked as signs of a mechanism of dangerousness that legitimates itself. The more you are stopped, even without a reason, the more they demonstrate you are dangerous. You can’t take your visiting friends and relatives around in town without them being stopped and ordered to show their documents.

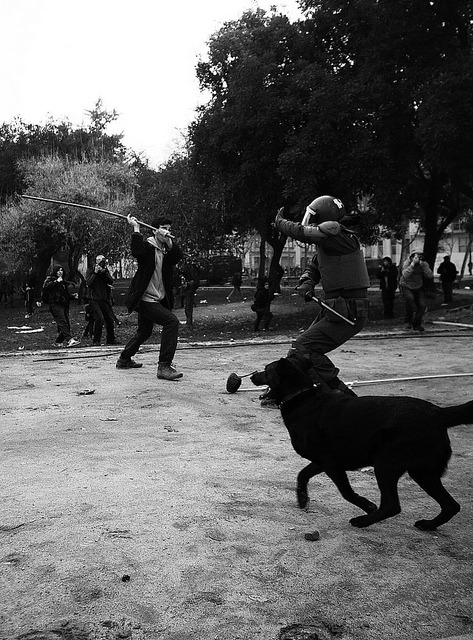

Moreover the atmosphere has now become very hot, and after the arrests carried out on April 6 in the operation ‘Outlaw’ against anarchists accused of organized crime, policemen in plain clothes don’t limit themselves to asking for documents but they make recourse to more rough-and-ready attitudes. They provoke you with rude gestures, push you, put their hands on you, ambush you outside your house in the night, make pressures on elderly parents and on your employers, and in the morning you can even find the wheels of your car or bike punctured after you were stopped the night before. Most worryingly, they invent accusations out of the blue for episodes that never occurred, thus leaving those who are persecuted at the mercy of a totally uncontrollable power.

It is a dangerous game. To face accusations fabricated by those who are right on principle puts you in a trap from which it is difficult to come out.

As these facts can be proved, here are a few examples. A comrade was stopped for five nights in a row, the first time she was kept in police custody and the other times she was kept in the street until dawn. Why? Because she was carrying some posters. On another occasion they waited for her in the night, outside her house, laying in wait behind a wall. Another comrade got three searches in a week, always with insubstantial results. Then there are those who have the Digos constantly outside their house, and when they go to the toilet or in whatever room, they see Digos agents peeking from behind the windows.

This relentlessness has something ridiculous, it seems that to find new forms of harassment has become the Digos’ life or death matter.

But this obsessive control leads to charges and police measures. No wonder, it runs in the family. Travel warrants in Bologna have reached the number of 16 for a single group of anarchists and others who showed solidarity. Oral Warnings [a sort of judicial notification], which urge to keep the peace otherwise you get a Special Surveillance order [another sort of judicial notification dating back to the Mussolini’s regime], have reached the number of 10. Two hearings for applying Special Surveillance orders were due in less than two months. The first one failed, the second one we still don’t know. If it gets approved, it will impose to stay indoors every night, not to leave the city, not to meet previous offenders and not to attend bettole [barrelhouses]. For a period that can last form 1 to 5 years.

You can sense it, power has fears. It is using preventive repression against those who have always struggled in order to give a signal to all the others. It is true, what we have just told concerns anarchists, but we don’t believe that such a treatment is going to be reserved to us only in these times of tension. To turn your back when repression hits others doesn’t save you from it striking at you, it could even turn into normal procedure.

The direction

The operation against the anarchists of Fuoriluogo has been orchestrated by the police and, very much likely, also by the Italian oil company [ENI], as proved by various press articles, and in particular by an interview with the ENI head of security published last May. Umberto Saccone mentioned ‘oil wells besieged by Al Quaida and by anarchists’ and he added that ‘in Bologna as well as in Florence police operations have been carried out, which have immediately contained this phenomenon’. Accustomed to repress in no uncertain terms the populations that rebel against the exploitation of themselves and of their resources, ENI couldn’t tolerate that its interests were under indictment even in its own country. In a crucial time when it finds itself in the necessity of reassessing its presence in northern Africa, ENI has no room for internal enemies. This is the only possible explanation for such a heavy and denigrating press campaign against the anarchists of a single city, which is still holding the stage in local and national newspapers and in weeklies, even if journalists have actually nothing to add to what they had published after the arrests in April. It needs a strong power behind editorial choices that certainly don’t even lead to any significant increase in sales, not to mention the very poor professional level displayed by journalists (from whom, as a matter of fact, we can’t expect nothing good and different). The daily ‘La Repubblica’ and the weekly ‘L’Epresso’ have distinguished themselves in this operation, but this is a natural consequence of their role of mouthpiece of the secret services. These papers keep close connections with the military security apparatus, which often gives them men to be recycled as mercenaries in defence of ENI and from which they drawn on information to be published every time the Italian colonial politics needs to be defended (their open support of the bombardments in Libya is emblematic in this sense).

http://325.nostate.net/?p=4041#more-4041

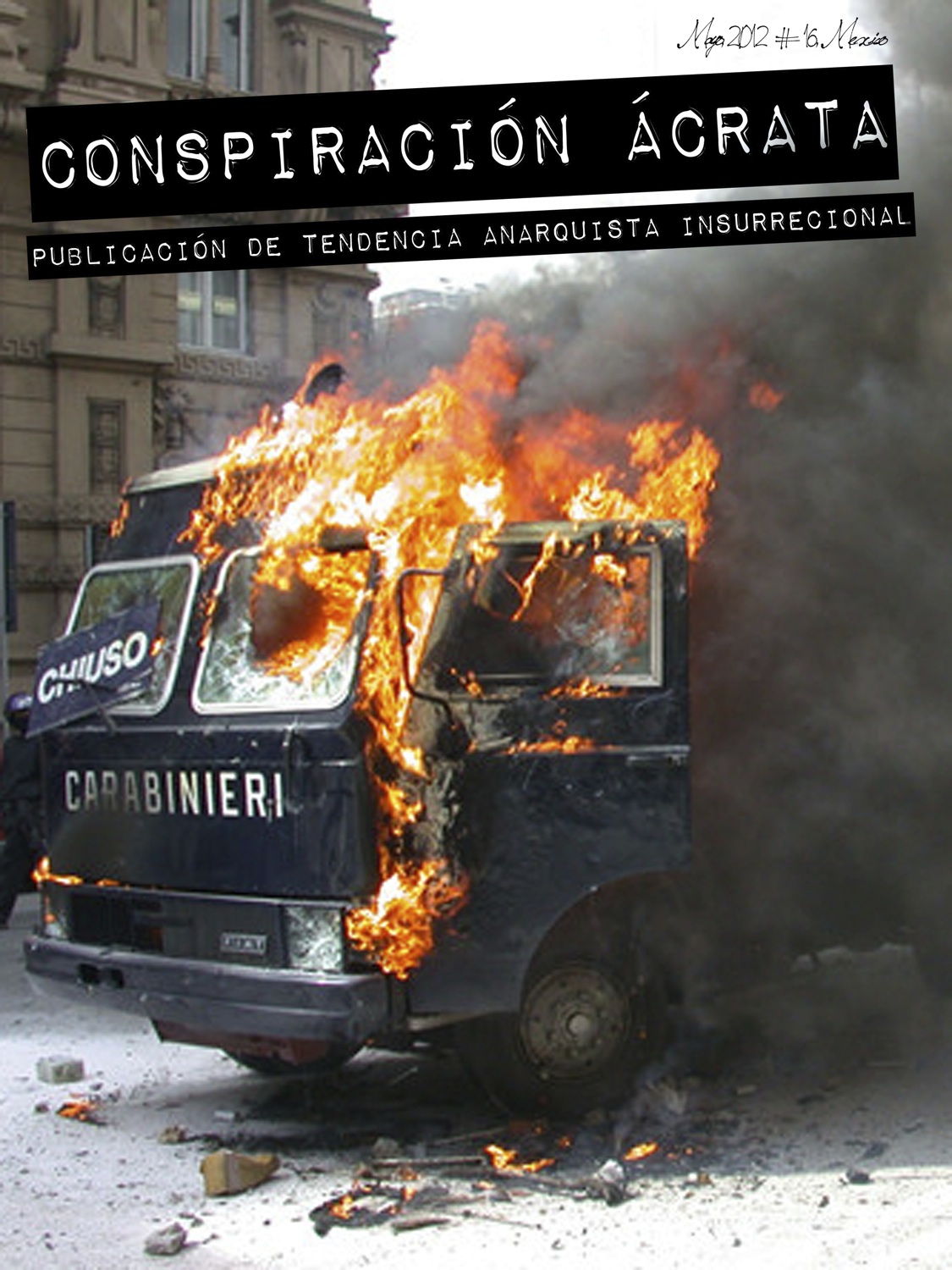

![Eurorepressione - Sulla conferenza a Den Haag sul tema "Anarchia" [corretto]](http://25.media.tumblr.com/tumblr_m0jvngOXtY1qa2163o1_1280.jpg)

![A tres años de la Partida de Mauricio Morales: De la Memoria a la Calle [Stgo.]](http://metiendoruido.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/mmacividad.jpg)

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento